Biochemistry Lab Techniques for the MCAT: Everything You Need to Know

/Master MCAT biochemistry lab techniques like chromatography, electrophoresis, and spectroscopy, plus practice questions with detailed answers.

Part 1: Introduction to biochemistry lab techniques

Part 2: Gel electrophoresis

a) Basic principles

b) Types

a. Native-PAGE

b. SDS-PAGE

c. Reducing SDS-PAGE

d. Isoelectric focusing

Part 3: Blotting methods

a) Basic principles

b) Types

a. Western blot

b. Southern blot

c. Northern blot

Part 4: DNA-based techniques

a) DNA sequencing via Sanger method

b) Polymerase chain reaction

a. RT-qPCR

b. cDNA library

Part 5: Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

a) Basic principles

b) Types

a. Direct

b. Indirect

c. Sandwich

Part 6: Molecular-biology techniques

a) Basic principles

b) Molecular cloning

c) Bacterial transformation

Part 7: Centrifugation and Chromatography

a) Basic principles

a. Gel filtration (size exclusion) chromatography

b. Ion-exchange chromatography

c. Affinity chromatography

Part 8: Biochemistry lab techniques high-yield terms

Part 9: Biochemistry lab techniques practice passage and answers

Part 10: Biochemistry lab techniques practice standalone questions and answers

----

Part 1: Introduction to biochemistry lab techniques

Welcome to our guide on experimental techniques in biochemistry. This is a high-yield topic, and a knowledge of the experimental techniques we will discuss will help you when you take your MCAT. One of the most difficult parts about learning these techniques is that they’re often presented at a very complex level, but we’ll provide concise and clear explanations in this guide. In many cases, it’s also easy to feel like you need to learn everything about an experimental technique to master these questions on the MCAT, but we’ll show you exactly what you need to know!

This is a long guide, but it’ll help you with the complex biochemistry techniques that the MCAT will throw at you. Remember, the MCAT test-writers develop passages by adapting scientific articles and asking you questions. By understanding these techniques, you’ll put yourself in the position to answer the diverse array of questions you may be asked on the exam.

We’re going to go into many of the techniques that may show up on your MCAT, including chromatography, molecular cloning, DNA sequencing, PCR, Blotting, ELISA, and gel electrophoresis. We’ll focus on the details that will help you ace these questions from an MCAT perspective, and we’ll finish with some sample questions to help you assess your proficiency.

(Suggested reading: MCAT Biochemistry: Everything You Need to Know)

----

Part 2: Gel electrophoresis

a) Basic principles

Gel electrophoresis is an experiment used to separate different components of a mixture based on their size and charge. Normally, these components are strands of DNA, RNA, or different proteins. Let’s say you have a test tube containing 5 different proteins, but you only want one of them. If the 5 proteins each have a different size (or different amino acids), you can separate them with gel electrophoresis.

During an experiment, you begin by placing your mixture on the gel, which you can think of as a large sheet of Jell-O. You then apply an electric field across the gel using a negatively charged side (cathode) and a positively charged side (anode). The molecules will travel through the Jell-O, and you can think of the system as a molecule swim meet through a Jell-O pool. (Note: many gel electrophoresis experiments are referred to with the acronym PAGE, or polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Polyacrylamide just refers to the type of gel that is used!)

All gel electrophoresis experiments work by taking advantage of three properties: size, charge, and shape.

1. Size

Let’s look at size first: pretend each of our 5 proteins has the same net negative charge. When you turn on the electric field, all 5 proteins will move towards the positively charged side of the electric field. However, the proteins are in the Jell-O, so if one protein is really big, it’ll move more slowly than the smaller proteins. (Think of walking through waist-deep water versus knee-deep water!) If you start the race by turning on the electric field, all the proteins will move towards the finish line, but the smallest will get there first. If you stop the race at any point by turning off the electric field, your proteins will stop moving.

2. Charge

While molecules are usually separated by just size, you need to remember that charge can also be a factor. Let’s say we start with 3 proteins of equal size. Protein 1 has a net charge of -5. Protein 2 has a net charge of -20. Protein 3 has a net charge of -40. Which protein will travel towards the positively charged anode more quickly? Protein 3 will travel towards the positive end of the gel faster than Proteins 1 and 2 because it is more highly charged and experiences greater attraction to the positive side. On the other hand, protein 1 will travel the slowest.

As we saw above, the total charge does vary for proteins, and this variation of charge is dependent on the protein’s side chains. Acidic side chains are negatively charged when deprotonated, while basic side chains are positively charged when protonated. If you add up all of these charges, you get a net charge that’ll tell you 1) how quickly the protein will move and 2) in which direction.

How does charge affect gel migration for nucleic acids? You might know that in the structure of DNA and RNA, each nucleoside or subunit (A, C, G, T, or U) is joined to the next using a link that contains a phosphate group. Importantly, each phosphate group carries a negative charge, so DNA and RNA will always be negative and will always be attracted to the positive charge. As a result, you can assume that every strand of DNA and RNA has a constant and equal distribution of charge or an equal charge density. For this reason, charge isn’t a factor when comparing how quickly different strands of DNA and RNA move, and it is only dependent on their size and shape.

3. Shape

The last big factor is molecule shape or aerodynamics. The more aerodynamic or streamlined a substance is, the faster it will move through the gel. Think of a race car that weighs the same amount as a school bus; the race car is more aerodynamically designed than the bus, so the race car still should travel faster than the school bus even if they weigh the same amount.

b) Types

a. SDS-PAGE

Since the charge density throughout a protein can vary, separating proteins is a little more complex than separating DNA or RNA. While smaller DNA and RNA strands will almost always travel faster than larger strands, proteins may break this general rule of thumb if they have different charge densities.

For example, you might have a large protein with a lot of negative side chains and a slightly smaller protein with fewer negative side chains. Will the larger protein travel faster because it is more negatively charged? Or will the smaller protein travel faster because it is smaller? Even for similarly sized and charged proteins, the 3D structure of the protein may vary a lot, meaning aerodynamics are another factor we might have to deal with.

In order to eliminate the effects of the differences in charge distribution and 3D shape for proteins that we mentioned above, researchers use SDS-PAGE. In other words, if you want to separate proteins just by their size (number of amino acids), use SDS-PAGE!

In SDS-PAGE, researchers add sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) to their proteins before running them on the gel. SDS denatures the protein and adds a number of negative charges that are proportional to the size of the protein, thereby creating an equal charge distribution (just like we see in DNA and RNA).

You can think about protein denaturing as untying a difficult knot. The primary structure of a protein is the string that was used to create the knot, and the secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures were created when you made that terrible knot, which is often necessary for protein function in our analogy. Adding SDS unties the knot, so you are left with an untied string containing a number of negative charges that are proportional to the length of the string. The shorter strings will always travel faster than the longer strings, and we no longer have to worry about charge!

Figure: SDS-PAGE gel

b. Reducing SDS-PAGE

There’s one small thing that we haven’t told you about SDS-PAGE yet: adding SDS completely denatures (or straightens) the protein except at places where there are disulfide bonds. Disulfide bonds are formed by the connection between two different cysteine side chains of a protein, and you can think of them as taping two points on a string together. This might cause the protein to travel more slowly than if these two points weren’t attached.

In order to break these disulfide bonds, you have to add a reducing agent that reduces the single disulfide S-S bond to two S-H bonds. This is known as reducing SDS-PAGE. By using reducing SDS-PAGE, you ensure that all of the higher structure of a protein has been eliminated, including any disulfide bonds.

c. Native-PAGE

Sometimes you want to analyze a protein in its natural state, but once a protein is denatured, it is often impossible to return it back to its normal or native shape (imagine untying a massive knot and then being told to re-tie that exact knot!). If you want to isolate a protein and conduct a study that would require the protein to be in its native shape (e.g., studying your protein’s activity after adding an inhibitor), you need to use native-PAGE. In native-PAGE, you do not add SDS or reducing agents, and the gel is non-denaturing, so the protein can remain in its native shape and maintain its secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structure.

Figure: Native, SDS-PAGE, and Reducing SDS-PAGE gels

d. Isoelectric focusing

In the 3 electrophoresis techniques we’ve discussed, you introduce your molecules near the negatively charged side (cathode) and watch them migrate towards the positively charged side (anode). However, we’ve already discussed that the net charge on proteins may also be neutral or even positive. If the net charge was positive, the protein would run the wrong way!

Let’s illustrate this problem by saying we have 3 proteins. Protein 1 has three negatively charged side chains (e.g., two aspartates and one glutamate) and one positively charged side chain (e.g., lysine). Let’s say protein 2 is completely neutral. And let’s say protein 3 has three positively charged side chains (e.g., lysine, arginine, and histidine). Protein 1 has a net charge of -2. Protein 2 has a net charge of 0. And Protein 3 has a net charge of +3.

If you place all 3 proteins on the negative end of the gel, only the negatively charged protein (Protein 1) will move (towards the positive side), and you wouldn’t have separated proteins 2 and 3. To solve this problem, we use a technique called isoelectric focusing.

Isoelectric focusing is similar to our previous experiments, except that there is a stationary pH gradient (ranging from about 0 to 14) inside the gel in addition to the electric field. The lowest pH is found near the positive side of the gel (anode), and the highest pH is found near the negative side of the gel (cathode). If you add components to this gel, they will migrate until reaching a region where the pH is equal to their isoelectric point, which is known as the pI. The isoelectric point is the pH at which the protein has a completely neutral charge.

How do we determine the isoelectric point of a protein? Let’s go back to those acidic and basic side chains. Acidic side chains will be deprotonated and negatively charged at a high pH. As you decrease in pH, however, more and more of these side chains will be protonated. In fact, most acidic side chains will be protonated by the time you get to a pH of about 2.

Basic side chains, on the other hand, will be protonated and positively charged at low pH. As you increase pH, more and more of these side chains will become deprotonated. Most basic side chains will be deprotonated by a pH of about 12. So, as you increase the pH, negative charges are gained whereas decreasing pH results in gaining positive charges.

The isoelectric point is the pH at which the number of negative charges is equal to the number of positive charges and your protein has a net neutral charge. Once your protein is neutrally charged, it will stop moving, and it won’t be attracted to the positive or negative poles of the gel!

Figure: Isoelectric focusing gel

----

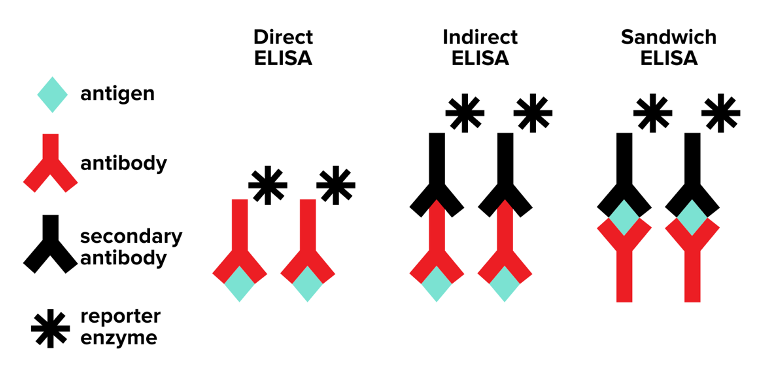

Part 3: Blotting methods

a) Basic principles

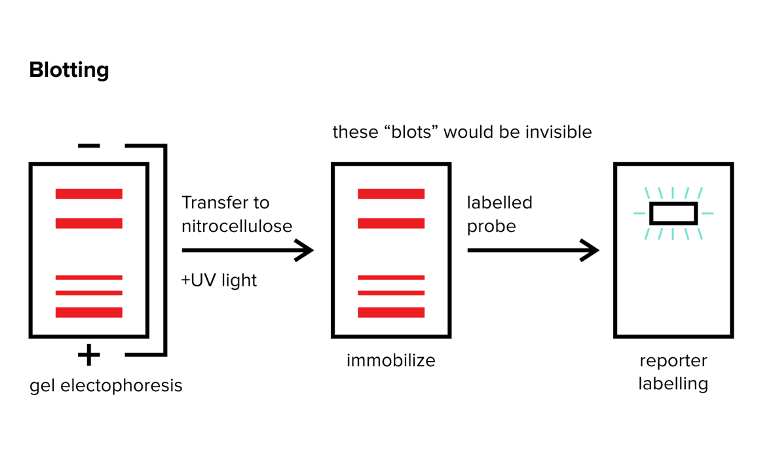

You’ve successfully separated mixtures of DNA, RNA, or proteins using gel electrophoresis—what’s next? In many cases, researchers are trying to identify specific strands of DNA or RNA or specific proteins. You can use various blotting methods to identify the specific DNA, RNA, or proteins that you are looking for. There are three general blots: Northern, Southern, and Western Blots. For each of these three techniques, you should be familiar with (1) the material that is being labeled (DNA versus RNA versus protein) and (2) the general technique that is used to label the target material.

Figure: Blotting methods. note: the red bands are invisible and need to be visualized with some reporter!

b) Types

a. Northern blot

You can use a Northern blot to identify the presence of a specific RNA strand in your sample. After using gel electrophoresis to separate RNA strands by size, you must transfer the RNA strands to another surface (nitrocellulose) and immobilize them to this surface using UV light. After the RNA is immobilized to the surface with UV light, you can introduce a labeling strand or probe to the already separated RNA strands, and the probe will specifically bind to the single RNA strand you are searching for. Note: the probe is often just an RNA strand that has a complementary sequence to the RNA strand you are looking for and a label so that you can visualize it!

In order to visualize the area where the probe has bound, the probe is generally labeled with a reporter. This reporter, which can take many forms, must be able to emit some sort of signal that can indicate where the probe is bound. In many cases, this reporter gives off colored light or a radioactive signal.

Let’s look at an example: you’ve just run a bunch of RNA strands on a gel that you isolated from the cells of a panel of cancer cells, and you want to determine if a specific transcription factor is being transcribed. You know the RNA sequence of the processed mRNA of the transcription factor is (5’-AGCCAAU-3’), but how are you going to determine if it is in your gel? You should immobilize the RNA strands to a nitrocellulose surface using UV light and add your labeled probe. Your probe should include the complementary RNA sequence (5’-AUUGGCU-3’: remember, the 3’ end of one strand binds to 5’ end of the other) bound to a reporter. You can then determine whether or not you obtain a reporter signal. If you see a reporter signal, the transcription factor is being transcribed in your gel.

b. Southern blot

A Southern blot is exactly like a northern blot except it involves DNA instead of RNA. After using gel electrophoresis to separate pieces of DNA, the DNA is still double-stranded. We want to use a probe like the one used in Northern blot, but we’ll first need to denature the double-stranded DNA into single-stranded DNA. That way, a probe with a complementary DNA sequence can actually bind. The rest of our steps are exactly the same!

c. Western blot

When you’re looking for a specific protein, you use a Western blot. The only difference between this technique and the technique used for Northern and Southern blotting is the type of probe used to search for a specific protein. Rather than using complementary strands of nucleic acids as we did in the other blotting techniques (there’s no such thing as a complementary strand to a protein), you need to use antibodies that recognize single proteins with high specificity.

In Western blotting, you generally use two antibodies. Your first antibody specifically binds to your target protein and is known as the primary antibody. Rather than labeling this antibody with a reporter, you use a labeled secondary antibody that recognizes your primary antibody. The secondary antibody is often labeled with a light-producing substance or radioactive substance as is the case for Northern and Southern blots. We conduct Western blotting as follows: gel electrophoresis -> immobilization of proteins -> primary antibody wash -> rinse away unbound primary antibodies -> secondary antibody wash -> rinse away unbound secondary antibodies -> look for signal.

Gain instant access to the most digestible and comprehensive MCAT content resources available. 60+ guides covering every content area. Subscribe today to lock in the current investments, which will be increasing in the future for new subscribers.

Figure: Northern, Western, and Southern blotting. Note: the nucleic acids are read from 5’ to 3’!

----

Part 4: DNA-based techniques

a) DNA sequencing via Sanger method

The Sanger method can be used to determine the sequence of a strand of DNA. What do we need to carry out Sanger sequencing? The method requires 5 basic ingredients: single-stranded DNA (template strand), a primer, DNA polymerase, deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs), and labeled dideoxynucleotide triphosphates (ddNTPs). You’ll also need four reaction tubes.

The single-stranded DNA is the DNA you are trying to sequence, and you can follow this description by looking at Figure 6. First, you must denature double-stranded DNA by heating in order to isolate the single-stranded DNA. The primer is a small piece of DNA that is complementary to (and binds to) the 5’ end of this single-stranded DNA. DNA polymerase then binds to the double-stranded region formed by the interaction between the single-stranded DNA and the primer, and it begins extending the primer by adding dNTPs complementary to the nucleotides on the template strand.

To jog your memory, the dNTPs are GTP, CTP, ATP, and TTP, and these are added to a DNA strand by DNA polymerase (remember: G is complementary to C and A is complementary to T). You may not have heard of labeled ddNTPs. These are identical to dNTPs except they do not contain a 3’ OH on the sugar, and each is uniquely labeled with a fluorescent reporter. For example, let’s say ddCTP is labeled teal, ddATP is red, ddTTP is blue, and ddGTP is yellow.

The polymerase continues adding dNTPs until it adds a ddNTP. The 3’ OH group on the ribose sugar must be present for the polymerase to add the next dNTP, but remember, the ddNTP does not have that 3’ OH group. As a result, the polymerase falls off, and the partial DNA strand is left unfinished. Importantly, the unfinished partial stand is labeled because we labeled each ddNTP, and the color of its label indicates the specific ddNTP that was added.

So, how does this work in an actual experiment? Let’s add the DNA we’re trying to synthesize, primer, DNA polymerase, and all four dNTPs to each reaction container and heat the containers to denature the DNA. Let’s also add one ddNTP to each reaction container (this is an important step: why?). In our experiment, let’s say we added ddCTP to reaction container 1. The DNA polymerase will go along extending the primer until it adds a ddCTP to the primer, which may occur (polymerase can also add a dCTP) when the DNA polymerase reaches a G nucleotide on the template strand. Imagine we’ve added about 1,000 DNA strands to this container and there are 5 G positions on the DNA strand. If we get the conditions right, it is possible to ensure that DNA polymerases add a ddCTP to different replicating strands at each of the 5 G positions. We would then have 5 labeled primers of differing lengths depending on where the G’s are in the template strand and the location at which the ddCTP was added. We can then run those primers on a gel to determine their relative length.

In order to determine the sequence of the DNA, we need to complete this experiment in each of four reaction containers using each ddNTP. Using this experiment, we should ideally have every possible unfinished strand labeled at the end by a ddNTP. We can then run the contents of each reaction container side by side on a gel, and the distance the primers will travel is indirectly proportional to their length. You can then easily determine the sequence as is shown in the picture of this gel. Remember, this sequence we obtain is complementary to our sequence of interest!

Figure: Sanger sequencing

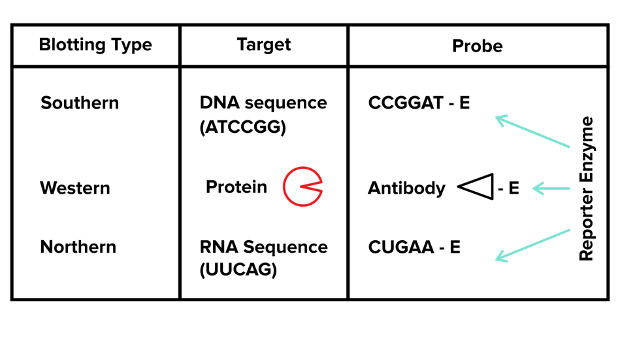

b) Polymerase chain reaction

a. RT-qPCR

RT-qPCR is a technique that can be used to generate many copies of an identical piece of complementary DNA (cDNA) from a small number of RNA transcripts. This cDNA can then be used for Sanger sequencing and many other applications. cDNA generally refers to a DNA strand that has been produced from messenger RNA and is complementary to the original mRNA. Remember, messenger RNA is found in the cytoplasm and is composed of the sequence used by the ribosome to produce a protein. The introns, or noncoding parts, of the RNA have already been removed by the time the mRNA exits the nucleus, so your cDNA doesn’t have the intron regions and is composed of just exons.

RT-qPCR stands for reverse transcriptase-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. “Reverse transcriptase” refers to the conversion of RNA to cDNA using a reverse transcriptase enzyme. “Quantitative” refers to us being able to measure how much DNA is actually being created. “Polymerase chain reaction” refers to how DNA is being magnified.

Let’s start with polymerase chain reaction and then work backward. If you have a double-stranded piece of DNA, you can produce many copies of this DNA using PCR. The PCR reaction requires very similar ingredients to those used in Sanger sequencing, except you don’t need the ddNTPs. You’ll add primers, DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and double-stranded DNA. For PCR, you need a primer, a short complementary piece of DNA, for both strands of DNA. You also need a heat-resistant DNA polymerase.

Let’s add the primers, DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and double-stranded DNA to a reaction container. If we do that (just as in the case for Sanger Sequencing), nothing will happen. Why? The primers will only bind to single-stranded DNA. First, we need to add heat (hence the heat-resistant DNA polymerase) that will denature the DNA, splitting it into two complementary single strands.

Now, we’ll lower the temperature again. The primers can bind to the single-stranded DNA in a step known as annealing. The temperature is then slightly raised again, and DNA polymerase will extend the primer using the dNTPs in a step known as extension or elongation.

As individual strands of DNA are extended, the single strands will bind to any complementary strands: a phenomenon known as hybridization. At the end of this step, the original strand of DNA will be replicated and there will be roughly double the DNA that we had before this first round of PCR. That is called a single round of PCR, and we just repeat the process, completing more rounds of PCR until we have the desired amount of DNA. The amount of DNA increases approximately as a factor of 2n where n is the number of PCR cycles.

Figure: How PCR works

In quantitative PCR, you want a more accurate quantification of how much DNA you are producing. This can be determined using a fluorescent probe that binds to double-stranded DNA. You can then measure the amount of fluorescence, which is directly related to the amount of double-stranded DNA. To complete RT-qPCR, you follow several steps:

1. Convert RNA to cDNA using reverse transcriptase

2. Magnify the amount of cDNA by completing rounds of PCR

3. Determine how much cDNA you have produced using a probe

b. cDNA library

A cDNA library is exactly what it sounds like: a library containing a bunch of different cDNA molecules that can be used for various applications. Creating a library of cDNAs might sound a bit more complicated than creating a library of books, but it really isn’t.

To build this library, you normally start with messenger RNA of a protein you are interested in. As we’ve already learned, mRNA doesn’t contain introns—it contains the exact sequence that is used by the ribosomes to create a protein. If you transcribe and translate cDNA, you can easily produce your protein of interest in a variety of host organisms. As a result, the cDNA library is essentially a library of protein-coding instructions.

How is a cDNA library built? First, you need to produce the cDNA from your mRNA. Similar to RT-qPCR, we use a reverse transcriptase enzyme to do this. Then, we insert the cDNA into a host cell genome. Once the cDNA is in the host cell’s genome, the host cells can express the protein on a large scale.

Gain instant access to the most digestible and comprehensive MCAT content resources available. 60+ guides covering every content area. Subscribe today to lock in the current investments, which will be increasing in the future for new subscribers.

----

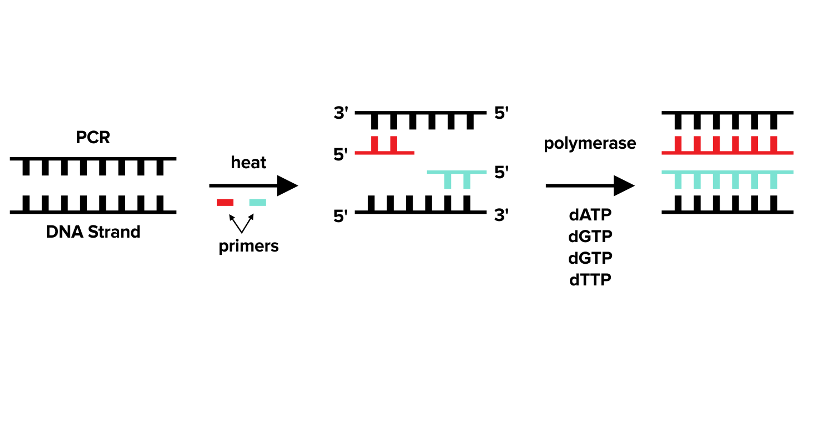

Part 5: Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

a) Basic principles

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay sounds intimidating, but don’t worry, we’ll teach you the basics of this technique here. Simply put, ELISA is used to determine if a protein, such as an antibody, binds to a specific antigen or to determine the concentration of antigen in a sample. These techniques involve immobilizing a substance to a surface, usually of a well plate, and rinsing a second substance over the immobilized substance to see if the two bind one another. To see if binding occurs, scientists use a reporting enzyme that generates a color change. There are three general types of ELISA you should be familiar with: direct, indirect, and sandwich.

b) Types

a. Direct ELISA

In direct ELISA, you follow three steps:

1. Antigen fixing: the antigen of interest is immobilized on a surface

2. Primary antibody binding: a liquid containing the primary antibody is washed over the immobilized antigen

3. Reporting: the reporter enzyme conjugated to the primary antibody creates a color change if binding occurs

b. Indirect ELISA

In indirect ELISA, you follow four steps:

1. Antigen fixing: the antigen of interest is immobilized on a surface

2. Primary antibody binding: a liquid containing the primary antibody is washed over the immobilized antigen

3. Secondary antibody binding: a secondary antibody that is specific to the primary antibody is introduced

4. Reporting: the reporter enzyme conjugated to the secondary antibody creates a color change if binding occurs

c. Sandwich ELISA

Sandwich ELISA is similar to direct and indirect ELISA, but it is instead used to determine how much antigen is present in a sample. For example, we can use sandwich ELISA to determine how much viral protein (an example antigen) is present in a blood sample.

Let’s think of sandwich ELISA as a simple hamburger ELISA. In a simple hamburger, you have a patty that is sandwiched between two buns. In sandwich ELISA, the buns are each an antibody, and the patty is the antigen, which is in between the two antibody buns. In sandwich ELISA, we already know the antibody that specifically binds to the antigen.

In sandwich ELISA, you follow four steps:

Antibody fixing: the antibody of interest is immobilized on a surface

Antigen binding: a liquid containing the antigen is washed over the immobilized antibody

Secondary antibody binding: a secondary antibody that is specific to the primary body is introduced

Reporting: the reporter enzyme conjugated to the secondary antibody creates a color change if binding occurs

If we get a large signal or a strong color change (high color saturation), we have a high concentration of bound antibody-reporter, which also indicates a high concentration of antigen in our original sample. If we get a small signal or a weak color change, our original sample had a low concentration of antigen.

Figure: ELISA

Genetic transformation and DNA technology have many applications in medicine and elsewhere. This technology can be applied in gene therapy to resolve inborn genetic mutations that cause illness or disease or to crops to provide pest and fungal resistance. It can also be used to produce pharmaceuticals by taking advantage of the molecular machinery in bacteria and fungi or in environmental cleanup operations involving bacteria modified to digest waste. Genetic sequencing has also been highly useful in analyzing forensic evidence.

These applications of DNA technology must be closely monitored for safety and ethical considerations.

----

Part 6: Molecular-biology techniques

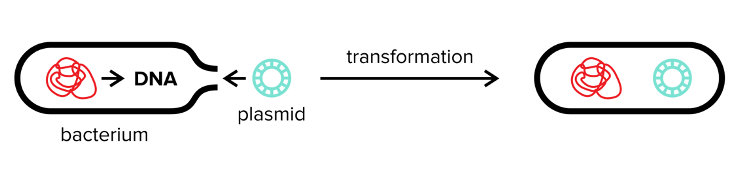

a) Bacterial transformation

We take advantage of many characteristics of bacteria for use in the lab. One of the most important is bacterial transformation. In natural bacterial transformation, a bacterium quite literally absorbs genetic information from its environment and incorporates that genetic information into its own genome. This process usually occurs when a bacterium undergoes stress, and the genetic information usually comes from other dead bacteria that have lysed (or ruptured). The new genetic information may code for genes that allow the bacteria to survive more easily.

We can also transform bacteria in the lab more specifically and with a gene of our choice. This is achieved by adding a plasmid, or a small, circular piece of DNA containing the gene of choice, to the bacterial environment. The bacteria can then express (transcribe and translate) the gene that the plasmid encodes. For example, let’s say we want certain bacteria to be resistant to an antibody. We take a plasmid containing a gene that confers this antibody resistance and add it to our bacterial colony. The bacteria that undergo transformation of this plasmid will be resistant to this antibody.

Figure: Bacterial transformation

b) Molecular cloning

Remember our discussion of the cDNA library? You should recall that creating a cDNA library involves storing a piece of cDNA that codes for a protein of interest in a host cell. You can also use the host cell to produce this protein on a large scale. In order to transfer your cDNA to the host cell, you can use molecular cloning!

To carry out molecular cloning, we first need to insert the sequence of interest into a plasmid, and we do this using restriction enzymes. Restriction enzymes (also known as restriction endonucleases) are special enzymes that cut DNA at palindromic sequences, creating short single-stranded regions. A palindromic sequence is a short sequence of double-stranded DNA (4-8 base pairs long) that reads the same both forward and backward (e.g., “racecar”). In the case of DNA, if you read one strand forward, the opposite strand will read the same sequence backward. Let’s look at the sequence 5’-GGATCC-3’. The opposite stand would have a complementary sequence: 5’-GGATCC-3’. Now if you read that backward, it reads 3’-CCTAGG-5’.

Restriction enzymes recognize a palindromic sequence and create a small break on each DNA strand. This creates two “sticky” single-stranded regions that can rebind via hydrogen bonding to their complementary sequences or to the same complementary sequence elsewhere. You can then seal the single-stranded nicks created by the restriction enzyme using DNA ligase. If we place the same palindromic sequence on both ends of our cDNA and our plasmid, we use a restriction endonuclease to create the sticky ends. Then, the sticky ends of the cDNA can bind to those of the plasmid, thereby generating a plasmid with the cDNA. We can then add the plasmid to a bacterial colony, and through transformation, the bacteria will incorporate the cDNA (and the rest of the plasmid) into its genome.

To ensure that our plasmid contains the cDNA, we can insert an antibiotic resistance gene into our plasmid alongside the cDNA. Now, our plasmid should have two separate important genes: one cDNA gene and one gene for antibiotic resistance. Any bacteria that successfully takes up the plasmid should be resistant to that antibiotic due to the expression of the antibiotic resistance gene. The bacteria that don’t have the antibiotic resistance gene will die.

Now, let’s make sure the plasmid actually has the cDNA gene, not just the antibiotic resistance gene. We can ensure our plasmids (and the bacteria) contain the cDNA gene by also including a reporter gene (such as LacZ) in the plasmid. When translated by the bacteria, this reporter gene will produce a signal.

The LacZ protein is an example of a reporter gene that can generate a color change for us. We should place our palindromic sequence (recognized by the restriction enzyme) inside this reporter gene. If the restriction enzyme cuts the palindromic sequence and the cDNA is inserted, the reporter gene will be interrupted by the cDNA gene and will not be translated into a functioning protein. If the cDNA is not inserted, the reporter gene will not be interrupted and will be translated into a functioning protein. In other words, if we add the LacZ substrate to our transformed bacteria and see a color change, we know the reporter gene is functioning and the protein doesn’t have our cDNA. If we add the LacZ substrate and don’t see a color change, it is likely that cDNA has successfully been introduced into our plasmid!

Figure: Molecular cloning

----

Part 7: Centrifugation and Chromatography

a) Basic principles

a. Centrifugation

Centrifugation is often used to separate substances of different sizes, densities, and lengths. The centrifuge spins a tube containing a liquid mixture with substances such as protein, DNA, and RNA. After rotating the tube at high speeds, denser substances and those with less surface area (more aerodynamic) will be found towards the side of the tube farther from the center of the centrifuge while less dense substances will be located towards the side of the tube nearer the center of the centrifuge.

Think of the dense substances as the clothes in your washing machine. You might have noticed that when you open the washing machine, all of the clothes are stuck to the inner walls of the washer machine, and they aren’t near the center of the washer machine. This is exactly what happens to the denser materials in your centrifuged mixture!

After you centrifuge a mixture, there are often two components in the tube. The first is known as the pellet, and it is a solid substance. As you might guess, you find the pellet at the end of the tube that was farther from the center of the centrifuge. This solid substance is formed as the dense particles reach the end of the tube and are stacked on top of each other. The second component is known as the supernatant. This component is liquid and is composed of less-dense particles.

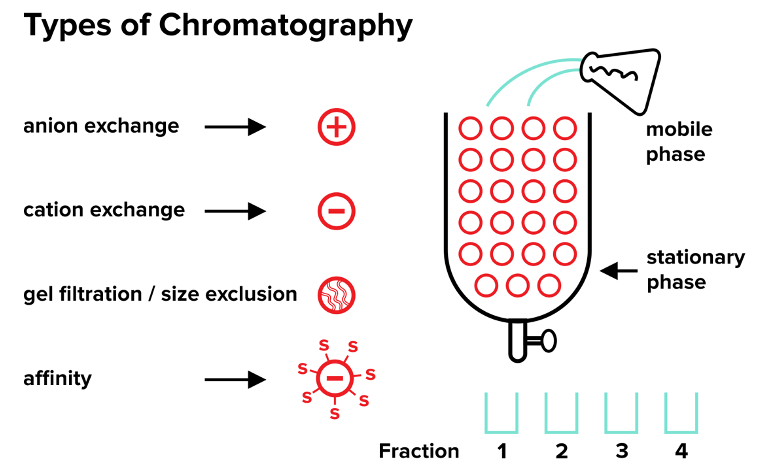

Scientists use centrifugation and chromatography to isolate specific molecules from a large mixture of other molecules. You normally start an isolation by using centrifugation, but in order to isolate a very specific substance, we often use various forms of chromatography. In each of the various forms of chromatography, you add your unpurified mixture, or mobile phase, to the top of a vertical column containing immobilized ions, beads, proteins, or other materials. These immobilized substances are called the stationary phase. The stationary phase never moves, and it remains fixed inside the column.

The substances in your mobile phase pass through your column because they are subject to gravitational forces, and you recollect portions of the mobile phase as they exit the bottom of the column in several different containers, or “fractions.” The first fraction will contain the materials in the mobile phase that traveled through the column the fastest while the last fraction will contain the materials that have traveled the slowest. The substances travel at different speeds based on their interactions with the stationary phase, and you choose the contents of the stationary phase based on what you are trying to isolate. Let’s look at a specific form of chromatography!

b. Gel filtration (size exclusion) chromatography

In gel filtration (size exclusion) chromatography, you separate components based on their size. To do this, you fix beads to your column to form the stationary phase. Size exclusion beads have tiny paths that only small particles can enter. When you pour your mobile phase through these beads, the large particles will pass through the column very rapidly because they won’t enter the beads, and you’ll find those larger molecules in the first fraction. The small particles will travel through the tiny paths in the beads. These paths are similar to a maze, so it will take longer for the small particles to reach the end of the column. As a result, the small particles will be found in the later fractions.

c. Ion-exchange chromatography

In ion-exchange chromatography, the stationary phase is composed of one type of charged ion (positive or negative). In anion-exchange chromatography, your stationary phase is composed of many positively charged substances that attract negatively charged (anionic) substances in the mobile phase. The name refers to the ion that is attracted to the stationary phase!

Likewise, in cation-exchange chromatography, your stationary phase is composed of many negatively charged substances that attract positively charged molecules in the mobile phase. The attracted substances will travel through the column more slowly than the other substances will.

The interaction between the molecules of the mobile phase and the stationary phase may end up being very strong. For example, in a cation exchange, the cations in the mobile phase may be so attracted to the negatively charged stationary phase that they don’t end up making it out of the bottom of the column. At that point, it is necessary to elute the cations, and elute is just a fancy word for “releasing from the column.”

d. Affinity chromatography

The last type of chromatography is known as affinity chromatography. For affinity chromatography, you use your stationary phase to attract a very specific substance in your mobile phase. For example, if you are trying to isolate a specific substrate from a mobile phase, you could immobilize the enzyme that binds the substrate in the stationary phase. The substrate will bind to the immobilized enzyme, and the rest of the mobile phase will pass through quickly.

The classic example (shown in the figure as well) is the protein streptavidin and its substrate biotin. Streptavidin is an enzyme that has an extremely high affinity for its substrate, biotin, which is a small molecule. So, you can coat the beads with immobilized streptavidin. If you’re trying to isolate biotin or any substance that you have linked to biotin, you can run the mobile phase containing biotin through the stationary phase with streptavidin, and you’ll capture your molecule of interest.

To summarize, in chromatography, you separate a substance of interest from a mixture by pouring a mobile phase containing your substance through a stationary phase containing something that will attract your substance of interest, slowing its travel through the column. If your substance doesn’t want to leave the column because it interacted strongly with your stationary phase, you must elute it.

Figure: Types of chromatography

----

Part 8: Biochemistry lab techniques high-yield terms

Gel electrophoresis: an experiment used to separate different components of a mixture based on their size and charge

Cathode: negatively charged side of a gel

Anode: positively charged side of a gel

PAGE (polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis): the material that often makes up the gel in gel electrophoresis

Charge density: the amount of charge per area of a molecule

SDS-PAGE: a specific type of gel electrophoresis where sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) is used to denature proteins and add a constant distribution of negative charges

Denature: to unfold a protein

Reducing SDS-PAGE: similar to SDS-PAGE although a reducing agent is used to break disulfide bridges

Disulfide bond: a covalent bond formed between two cysteine residues

Native-PAGE: a type of gel electrophoresis that does not denature the proteins, which will retain their secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structure

Isoelectric focusing: a type of gel electrophoresis used to separate proteins by their isoelectric point (pI)

Isoelectric point (pI): the pH at which the net charge of a protein is zero

Northern blot: a technique used after gel electrophoresis to identify a specific RNA strand

Reporter: an enzyme, fluorescent or radioactive compound, or other substance that sends a readily observed or measurable signal that is used to report the presence of another substance that is difficult to visualize

Southern blot: a technique used after gel electrophoresis to identify a specific DNA strand

Western blot: a technique used after gel electrophoresis to identify a specific protein

Primary antibody: the first antibody that binds a target protein

Secondary antibody: an antibody with a fluorescent label or conjugated enzyme that binds to the primary antibody

Sanger method: a technique used to determine the sequence an of DNA strand

Primer: a small, single-stranded piece of DNA or RNA that binds to the 3’ end of a piece of DNA and is necessary for the initiation of DNA replication by DNA polymerase

Reverse transcriptase: an enzyme that produces a strand of DNA that is complementary to an RNA strand

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR): a method used to generate a large number of copies of a piece of DNA

cDNA library: a collection of host cells, usually bacteria, that is used to store genes of interest

Indirect ELISA: a type of ELISA where you immobilize an antigen and determine if an antibody binds to it, followed by a secondary antibody linked to a reporter enzyme to determine if binding has occurred

Direct ELISA: a type of ELISA where you immobilize an antigen and determine if an antibody binds to it, and a reporter enzyme linked to the antibody tells you if binding has occurred

Sandwich ELISA: a type of ELISA where you determine the concentration of an antigen in solution by immobilizing an antibody, adding the antigen, and then adding additional antibody that is linked to a reporter enzyme

Bacterial transformation: the process of a bacteria absorbing genetic information from its surroundings and inserting it into its genome

Plasmids: circular pieces of DNA

Restriction enzymes/endonucleases: enzymes that cut specific palindromic sequences of DNA

Centrifugation: separating substances by spinning them at high speeds

Pellet: the solid region at the bottom of a centrifuged tube containing dense substances

Supernatant: the liquid region at the top of a centrifuged tube containing less dense substances

Chromatography: a technique used to isolate a substance of interest from a larger mixture of molecules

Mobile phase: the liquid containing your substance of interest in chromatography

Stationary phase: the immobilized part of the column that will attract your substance of interest in chromatography

Gel filtration (size exclusion) chromatography: a type of chromatography where you use beads with many small paths as your stationary phase to separate contents of a mobile phase by size

Ion-exchange chromatography: a type of chromatography where you use a positively or negatively charged stationary phase to separate contents of a mobile phase by charge

Anion-exchange chromatography: a form of ion-exchange chromatography that attracts negatively charged molecules

Cation-exchange chromatography: a form of ion-exchange chromatography that attracts positively charged molecules

Elute: breaking the interaction between your substance of interest and the stationary phase so that your substance of interest exits the column

Affinity chromatography: a type of chromatography where you isolate a specific substance from the mobile phase by using a stationary phase that contains something with a high affinity for your substance of interest

----

Part 9: Biochemistry lab techniques practice passage and answers

Researchers have shown that radiation therapy has significant immune modulatory effects and is capable of unleashing potent anti-tumor CD8+ T cell responses. Radiation therapy has been shown to enhance the efficacy of various T cell-targeted immunotherapies that improve antigen-specific T cell expansion, T regulatory cell depletion, or effector T cell function. The ability of radiotherapy to enhance adaptive immune responses has further been highlighted by the PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade in preclinical models of CD8+ T cells. Several proteins in this checkpoint blockade are activated by RVF3, a small binding protein indicative of radiation-induced damage, including the TMRa inhibitor, which is activated at nanomolar concentrations of RVF3.

While interest in abscopal effects, or those observed outside of the field of irradiation, have increased in part due to the observation that radiation can act as an in situ vaccine, researchers have recently determined that combinational radiation and checkpoint blockade therapy requires pre-existing T cell responses to control tumors. Given the strong interest in using existing therapies such as radiation to enhance αPD-1/αPD-L1 responses in human cancers, it is critical to understand the mechanisms by which RT is improving outcomes to better inform the treatment of patients.

In this study, researchers set out to determine, in checkpoint inhibitor-resistant models, which components of radiation are primarily responsible for overcoming this resistance. In order to model the vaccination effect of radiation, researchers used a Listeria monocytogenes-based vaccine to generate a large population of tumor antigen-specific T cells but found that the presence of cells with cytotoxic capacity was unable to replicate the efficacy of radiation combined with the checkpoint blockade. However, researchers did demonstrate that a major role of radiation was to increase the susceptibility of surviving cancer cells to CD8+ T cell-mediated control through enhanced MHC-I expression. Researchers also discovered that treatment with interferon-gamma (IFNγ) increased MHC-I expression as shown in Figure 1 and improved susceptibility of cancer cells to control by antigen-specific CD8+ T cells.

Figure 1: Quantification of MHC-I expression of certain surface receptors of pancreatic cancer cell lines with and without (NT) 72 hours of IFNγ stimulation. Key: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001.

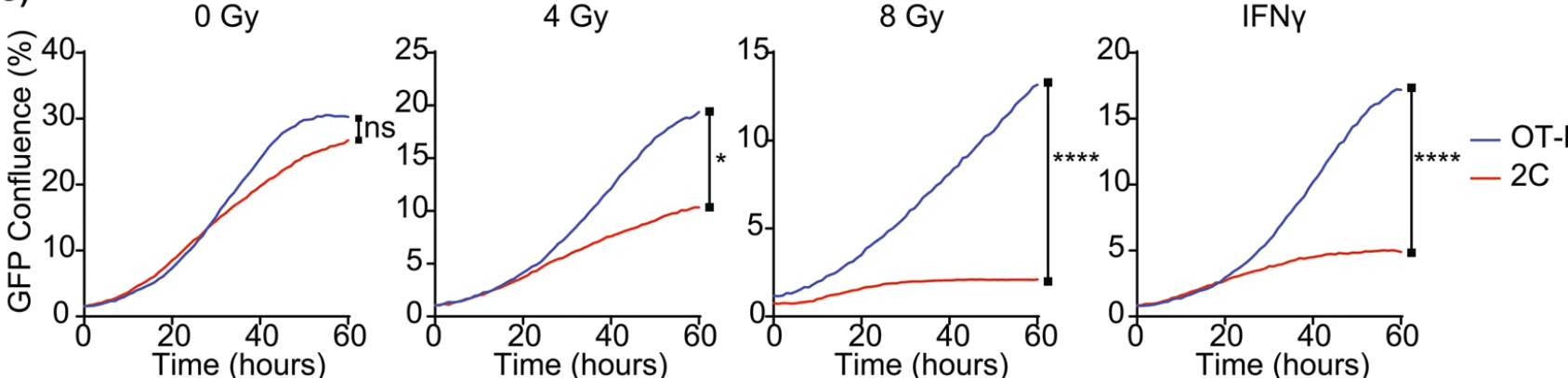

Researchers also observed a novel mechanism of genetic induction of MHC-I in cancer cells through upregulation of the MHC-I and its transactivator SIY and found significant differences in the induction responses of 2 cell lines after treatments with radiation and IFNγ (Fig. 2). In order to perform this assay, researchers first constructed a fusion of GFP and the model antigen, SIY, to determine the level of expression of SIY. Researchers then examined a potential relationship between this response and the αPD-1/αPD-L1 response. The data supports the critical role of local modulation of tumors by radiation to improve tumor control with combination immunotherapy.

Figure 2: The GFP Confluence of Panc02SIY100 cancer lines, OT-1 and 2C following pretreatment with in vitro irradiation or IFNγ. GFP Confluence is proportional to SIY expression. Key: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001

CREATOR AND ATTRIBUTION PARTY: ZEBERTAVAGE, L., ALICE, A., CRITTENDEN, M., ET AL. TRANSCRIPTIONAL UPREGULATION OF NLRC5 BY RADIATION DRIVES STING- AND INTERFERON-INDEPENDENT MHC-1 EXPRESSION ON CANCER CELLS AND T CELL CYTOTOXICITY. SCI REPORTS 10, 7376 (2020). THE ARTICLE’S FULL TEXT IS AVAILABLE HERE: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-64408-3. THE ARTICLE IS NOT COPYRIGHTED BY SHEMMASSIAN ACADEMIC CONSULTING. DISCLAIMER: SHEMMASSIAN ACADEMIC CONSULTING DOES NOT OWN THE PASSAGE PRESENTED HERE. CREATIVE COMMON LICENSE: HTTP://CREATIVECOMMONS.ORG/LICENSES/BY/4.0/. CHANGES WERE MADE TO ORIGINAL ARTICLE TO CREATE AN MCAT-STYLE PASSAGE.

Question 1: The researchers discover that they accidentally mixed up two cancer lines, OT-1 and 2C, but they were able to identify 2C because its genome contains a unique, highly repeated DNA sequence: 5’-ACCGCCTCCTCCC-3’. What sequence could the researchers use in their Southern blot probe to identify this cell line?

A) 5’-TGGCGGAGGAGGG-3’

B) 5’-ACCGCCTCCTCCC-3’

C) 5’-GGGAGGAGGCGGT-3’

D) 5’-CCCTCCTCCGCCA-3’

Question 2: What was the role of GFP in this study?

A) GFP functioned as a reporter enzyme to indicate the level of translation of another protein.

B) GFP allowed for the visualization of areas on the CD8+ T cells where radiation caused mutations.

C) GFP increased the susceptibility of OT-1 to irradiation and IFNy after 20 hours.

D) GFP was used as a control to compare to the binding of SIY.

Question 3: Researchers have discovered a method to synthesize the NLRC5 cell receptor, which conveniently has an extremely short amino acid sequence. The researchers vaccinated mice with the receptor and isolated an antibody that is highly expressed in these mice compared with controls. What technique should researchers use to determine if the antibody expressed effectively binds to this receptor?

A) Polymerase chain reaction

B) Indirect ELSA

C) Southern blot

D) Sandwich ELISA

Question 4: Researchers have isolated a particularly robust strain of OT-1 cancer cells that exhibit a high level of potency immediately after radiation therapy. Researchers want to look for the mRNAs of three different cell cycle activators expressed in this line with several other OT-1 lines. What technique should researchers use?

A) Centrifuge followed by Southern blot

B) Reverse transcriptase followed by PCR and gel electrophoresis

C) Centrifuge followed by Northern blot

D) Reverse transcriptase followed by PCR

Answer key for biochemistry lab techniques practice passage

1. Answer choice C is correct. DNA has a distinct polarity (5’ to 3’) and strands bind in an antiparallel fashion. DNA sequences are always read from 5’ to 3’ unless otherwise stated. So, you need to design a complementary DNA strand to this sequence to use in the probe. To do this, switch the A’s and T’s, G’s and C’s. Then you need to invert the sequence (read it backward) for it to read 5’ to 3’ (choice C is correct; choices A, B, and D are incorrect).

2. Answer choice A is correct. The passage states that GFP and SIY were fused to determine the level of expression of SIY (choice A is correct; choice D is incorrect). While GFP is a fluorescent protein and can be used for visualizations, the passage focuses on cancer cells, not the CD8+ T cells. The passage also mentions that SIY is upregulated in cancer cells (choice B is incorrect). The results shown in Fig. 2 disprove the idea that GFP increases the susceptibility of OT-1 to irradiation and IFNy after 20 hours (choice C is incorrect).

3. Answer choice B is correct. Using indirect ELISA, you can immobilize the NLRC5 receptor, add the antibody, and then use a secondary antibody with a reporter enzyme that binds to the primary antibody (choice B is correct). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is used to amplify a specific piece of DNA (choice A is incorrect). Southern blots are used to label DNA, but the question stem is asking about two different proteins (choice C is incorrect). Sandwich ELISA is used to determine the concentration of an antigen once the binding interaction between the antigen and the antibody has already been established. It can also be used to prove a binding interaction. However, the question stem stated that the protein is extremely small, which might make it impossible to bind two separate antibodies to NLRC5. As a result, the result might be negative even if the antibody binds (choice D is incorrect).

4. Answer choice C is correct. Centrifugation is a logical first step that will help remove a variety of contaminants (choices B and D are incorrect). Northern blots are used for RNA while Southern blots are used for DNA (choice C is correct; choice A is incorrect).

Want more MCAT Practice Questions? Check out our proprietary MCAT Question Bank for 4000+ sample questions and eight practice tests covering every MCAT category.

Gain instant access to 4,000+ representative MCAT questions across all four sections to identify your weaknesses, bolster your strengths, and maximize your score. Subscribe today to lock in the current investments, which will be increasing in the future for new subscribers.

----

Part 10: Biochemistry lab techniques practice standalone questions & answers

Question 1: Which of the following DNA sequences is most likely to be recognized by a restriction endonuclease?

A) 5’-AACCAA-3’

B) 5’-ACATGT-3’

C) 5’-ATATCGC-3’

D) 5’-GACGAC-3’

Question 2: Which of the following techniques would you most likely use to isolate a protein with a net positive charge of +35?

A) Size exclusion chromatography

B) Gel filtration chromatography

C) Anion-exchange chromatography

D) Cation-exchange chromatography

Question 3: Which of the following is not used in PCR?

A) ddNTPs

B) Heat-resistant DNA polymerase

C) Double-stranded DNA

D) Two primers

Question 4: A bond formed between which of the following amino acids is disrupted in reducing SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis?

A) Histidine

B) Cysteine

C) Leucine

D) Methionine

Answer key for biochemistry lab techniques practice standalone questions

1. Answer choice B is correct. Restriction endonucleases recognize palindromic sequences of double-stranded DNA, generally between 4 and 8 bases long. A palindromic sequence of DNA reads the same way from 5’ to 3’ on both strands of DNA. You need to determine which one of these sequences has a complementary sequence like this. While A looks like a “palindrome,” it is not a palindromic sequence of DNA. The complementary sequence read 5’ to 3’ is read TTGGTT. The complementary sequence of B is read TGTACA from 3’ to 5’, but it is read ACATGT from 5’ to 3’.

2. Answer choice D is correct. Cation-exchange chromatography is used to isolate positively charged substances from the mobile phase (choice D is correct; choices A, B, and C are incorrect).

3. Answer choice A is correct. PCR is used to amplify a double-stranded piece of DNA (choice C is incorrect). ddNTPs, which have an H instead of an OH at the C’3 carbon, prevent DNA polymerase from adding additional nucleotides (choice A is correct). A heat-resistant DNA polymerase is needed to synthesize new DNA (choice B is incorrect). Two primers—one complementary to the 3’ end of each DNA strand—are needed (choice D is incorrect).

4. Answer choice B is correct. Cysteine forms disulfide bonds, which are broken in reducing SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis (choice B is correct; choices A, C, and D are incorrect).