Enzymes for the MCAT: Everything You Need to Know

Learn everything you need to know about enzymes—one of the most heavily tested science topics on the MCAT

(Note: This guide is part of our MCAT Biochemistry series.)

Part 1: Introduction to enzymes

Part 2: General enzyme characteristics

a) Catalytic activity

b) Enzyme-substrate binding

c) Types of enzymes

d) Cofactors, coenzymes, and vitamins

e) Catalytic amino acids

Part 3: Enzyme kinetics and inhibition

a) Michaelis-Menten and Lineweaver-Burk

b) Competitive inhibition

c) Uncompetitive inhibition

d) Mixed and noncompetitive inhibition

Part 4: Regulating enzyme activity

a) Local environment conditions

b) Covalent modification

c) Allosteric regulation

d) Zymogens

e) Cooperativity

f) Feedback regulation

Part 5: High-yield terms

Part 6: Enzymes practice passage

Part 7: Enzymes practice questions and answers

----

Part 1: Introduction to enzymes

Enzymes are one of the most heavily tested science topics on the MCAT, and they are an important part of our everyday life. Each cell in our body carries out many of its functions using enzymes, and misregulation of these enzymes is responsible for a wide scope of human diseases, such as cancer and hypertension.

Many students struggle with enzymes on the MCAT, often losing valuable points on questions testing topics from enzymatic inhibition to feedback regulation. In this guide, we will break down the content you need to know—no more and no less—to study enzymes for the MCAT. All of the terms bolded throughout the guide will be defined in Part 5 of the guide, but we encourage you to create your own definitions and examples as you move through this resource so that they make the most sense to you!

In addition to knowing the content, you will also need to know how to analyze the various graphs, equations, and terms related to enzymes that the MCAT presents. At the end of this guide, there is an MCAT-style enzyme practice passage and standalone questions that will both test your knowledge and show you how the AAMC likes to ask questions.

Let’s get started!

----

Part 2: General enzyme characteristics

a) Catalytic activity

Enzymes are biological catalysts, and a catalyst is defined as a substance that speeds up the rate of a chemical reaction without being consumed itself. For example, let’s say you need to get from point A to point B, and they are 10 miles apart. You could walk, which would likely take a while. Or you could drive a car and arrive a lot faster. In this case, the car serves as our catalyst. Note, the distance is not changing, but the speed with which you get there is faster.

Figure: a catalyst is a substance that speeds up the rate of a chemical reaction, in the same way that a car helps you get from point a to point b faster

In the same way that a car speeds up our transportation, an enzyme serves to speed up the rate of a biochemical reaction. As a result, an enzyme is classified as a biological catalyst, which has the following properties (we will dive into each one):

Lowers activation energy of a reaction

Affects the kinetics of the reaction, but not the thermodynamics (∆G) or equilibrium constant

Regenerates itself

Let’s first look at activation energy. Which of the following requires us to put in more energy: walking or driving 10 miles? If you said walking, you are correct. (In a car, all we have to do is press the gas pedal!) An enzyme—the car in our example—reduces the amount of input energy necessary to undertake a chemical reaction. By lowering the input energy, or activation energy, of a reaction, the reaction can occur much more quickly. This brings us to reaction kinetics.

An enzyme affects the kinetics of a reaction by speeding up the rate of the reaction. Note, the reaction rate is the rate at which reactants are consumed or the rate at which products are made. Importantly, enzymes DO NOT affect the thermodynamics (∆G) or equilibrium constant of a reaction.

Let’s look at another example to illustrate this point. We have a machine that converts red spheres into red cubes. Normally, if you give the machine 10 red spheres, it will produce 5 red cubes in 1 hour. Now, let’s say a catalyst acts on the machine—if you give the machine 10 red spheres, it will produce 5 red cubes in 1 minute.

The kinetics of the machine are affected as it can now work faster, but the thermodynamics and equilibrium constant stay the same. In each case, 10 red spheres are made into 5 red cubes, regardless of how fast the machine can do it.

We’ve illustrated these effects below in a commonly drawn reaction diagram:

Figure: A free energy versus reaction progress plot showing the effect of a catalyst on activation energy for a reaction

Finally, enzymes are regenerated during their catalytic cycles. This is very important as regeneration reduces the amount of protein that a cell has to make in order to carry out biochemical reactions. For example, cells use a lot of ATP, and most of this ATP is generated by ATP synthase, an enzyme. (As a brief aside, enzymes often end with an -ase!) If each ATP synthase could only synthesize one ATP molecule, the cell would be overrun by the ATP synthase enzymes. The ability of each ATP synthase—and other enzymes—to reset itself after each cycle is absolutely essential to our survival.

In the figure below, we show you how regeneration would make a great difference in the number of ATP synthases needed for a cell if it could not regenerate itself for multiple catalytic cycles.

Figure: why enzyme regeneration is important

b) Enzyme-substrate binding

We’ve talked about the general properties of enzymes, and now we will dip our toes into more of the nitty-gritty details. We often talk about chemical reactions by writing out reaction schemes such as A → B → C. For enzymes, we can draw out a reaction scheme that can help us better understand what exactly is going on, and it looks something like the following:

E + S → ES → E + P

E = enzyme

S = substrate

P = product

We’ll come back to the overall reaction scheme when we look at enzyme inhibition in the next section, but let’s zoom into the ES, or enzyme-substrate complex.

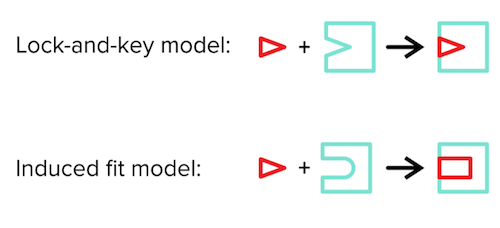

There are two models for describing the enzyme-substrate complex: 1) the lock-and-key model and 2) the induced fit model. The lock-and-key model describes the substrate as the “key” and the enzyme as the “lock.” Without changing any conformations, the key should fit nicely into the lock for the two to bind.

The induced-fit model (which is generally the more accepted model) states that enzyme and substrate conformations do not have to be as rigid as suggested by the lock-and-key model. Instead, upon substrate binding to the enzyme, both will undergo slight conformational changes to improve their binding to one another.

Figure: lock and key model vs induced fit model

c) Types of enzymes

There are six well-known types of enzymes that the MCAT wants you to know:

| Enzyme type | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|

d) Cofactors, coenzymes, and water-soluble vitamins

Most enzymes require small ions or proteins to help them function properly. Cofactors/coenzymes usually bind to the enzyme’s active site and assist in catalyzing the reaction. The two are essentially the same, except coenzymes are proteins whereas cofactors can be ions, such as Mg2+. Water-soluble vitamins may also play roles in enzymatic activity, and they have to be obtained from our diets.

If the cofactor or coenzyme is bound extremely tightly to the enzyme, it is called a prosthetic group. With their cofactors or coenzymes, enzymes are called holoenzymes, and without cofactors or coenzymes, enzymes are called apoenzymes.

e) Catalytic amino acids

You should know the one-letter code, three-letter code, and structures for all 20 amino acids. If you don’t, now is a good time to learn them as they are virtually guaranteed to show up in some capacity on the MCAT.

Now that you know the amino acids, we have a question for you: Is an arginine or a valine more likely to be a catalytically important amino acid based on what you know about its structure and chemical properties?

If you said arginine, you are correct. Since you know all of the above-mentioned properties about each of the 20 amino acids, you know exactly what chemical properties each amino acid displays. In general, charged, polar, or nitrogen-containing amino acids are more likely to be involved in the catalytic steps of an enzyme. Why? These amino acids have interesting properties that allow them to carry out chemistry with the substrate. For example, a lone pair on a terminal nitrogen in lysine can serve as a nucleophile. (For more information on electrophiles and nucleophiles, be sure to refer to our guide on the fundamentals of organic chemistry.)

Nonpolar and hydrophobic amino acids are less likely to be catalytically important amino acids as they cannot directly engage in interesting chemistry. Valine does not have any atoms that are highly electrophilic or that want to serve as nucleophiles. As a general rule of thumb, nonpolar and hydrophobic amino acids are more important in protein-protein interactions and forming the core of a protein, not in carrying out biochemical reactions.

----

Part 3: Enzyme kinetics and inhibition

a) Michaelis-Menten and Lineweaver-Burk

Michaelis-Menten

You will need to be familiar with analyzing two major plots when it comes to enzymes. The first is the Michaelis-Menten plot. In order to generate a Michaelis-Menten plot, experimenters use two very specific conditions:

Enzyme concentration is held constant

Substrate concentration is increased

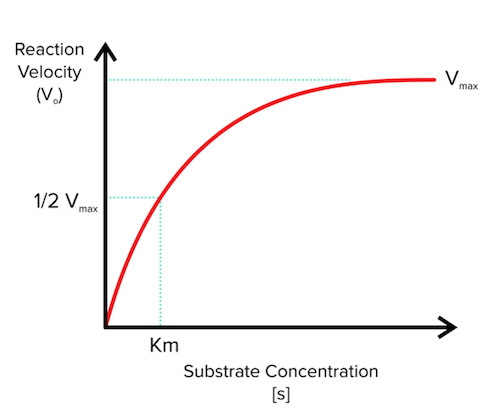

Researchers then plot the reaction velocity, or how fast the reaction is going, versus the increasing substrate concentration. So, if we have 100 enzymes, the researchers might measure reaction velocity in the presence of 10-500 substrates, increasing by 10 substrates for each reaction velocity measurement. Let’s look at a Michaelis-Menten plot:

Figure: A Michaelis-Menten graph

The two big values that you will need to keep in mind are vmax and Km, and these will become especially important when we begin talking about inhibition in the next section.

As substrate concentration increases along the x-axis, you might notice that the curve begins to flatten out as it reaches vmax. We define vmax as the maximum speed at which the reaction can proceed given the current concentration of enzyme and the speed with which the enzymes work. Think back to our specific conditions—we determine the amount of enzyme that we use in the experiment and hold it constant throughout.

We can state the exact same concept in equation form, and you should be familiar with the following equation for the MCAT:

The equation shows that vmax is simply the maximum speed of all of the enzymes combined, and it is calculated by multiplying the concentration (or number) of enzymes by how fast each one works.

Now, why does vmax even appear? At a certain point, the amount of substrate is so great that the enzymes are already working as fast as they can. Once we reach this point of saturation, the addition of any new substrate will not make a difference in how fast the enzyme can work.

For example, let’s say a machine can create 10 new pencils from 10 pieces of wood every minute. We are running an experiment in which we add pieces of wood and measure the output after a minute. If we add 1 piece of wood, the machine can take care of it quickly and produce a single pencil. If we add 5 pieces of wood, the machine produces all 5 pencils in a minute. If we add 10 pieces of wood, the machine is working as quickly as it can and will produce 10 pencils in a minute. If we add 2,000 pieces of wood, the machine cannot make all 2,000 pencils in a minute. In fact, it will only still be able to produce 10 pencils per minute. This saturation principle works the exact same way with enzymes; once you reach the point of saturation by adding too much substrate (wood in our example), the enzymes can’t increase production further since they are already working at their maximum rate.

Finally, let’s look at Km on the Michaelis-Menten plot, which is defined as the substrate concentration at ½ vmax. We can think of Km as the binding affinity of the substrate for the enzyme. Naturally, if the substrate can bind the enzyme with a higher affinity, it is more likely to be “captured” by the enzyme and converted into the product. A small Km indicates a high substrate affinity, and a large Km indicates a low substrate affinity.

Now that we know Km, let’s define one final term: catalytic efficiency. Catalytic efficiency describes how effective an enzyme is at converting substrate to product, and it is defined as:

Remember, kcat describes the speed of an individual enzyme, so the higher the speed, the better the efficiency. Km describes the affinity of the enzyme to the substrate, so the lower the Km, the better the efficiency.

Gain instant access to the most digestible and comprehensive MCAT content resources available. 60+ guides covering every content area. Subscribe today to lock in the current investments, which will be increasing in the future for new subscribers.

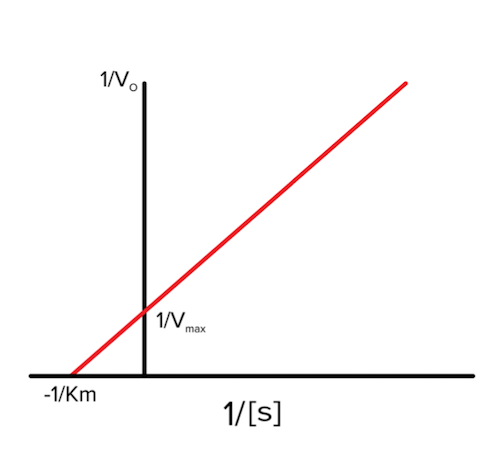

Lineweaver-Burk

Lineweaver-Burk plots show the exact same data as Michaelis-Menten plots, but they are simply graphed in a different way by taking the reciprocal of each axis on the Michaelis-Menten plot. What does this mean? The x-axis changes from [S] on the Michaelis-Menten plot to 1/[S] on the Lineweaver-Burk plot, and the y-axis changes from v 0 on the Michaelis-Menten plot to 1/v 0 on the Lineweaver-Burk plot.

Figure: Lineweaver-Burk plot

Vmax and Km are seen on the Lineweaver-Burk plots, but they are also shown as their reciprocal. These plots will become very important in the next section!

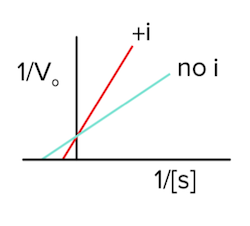

b) Competitive inhibition

For each type of inhibition, you should be able to answer these three questions:

1) What happens to the Vmax?

2) What happens to the Km?

3) What does the Lineweaver-Burk plot look like?

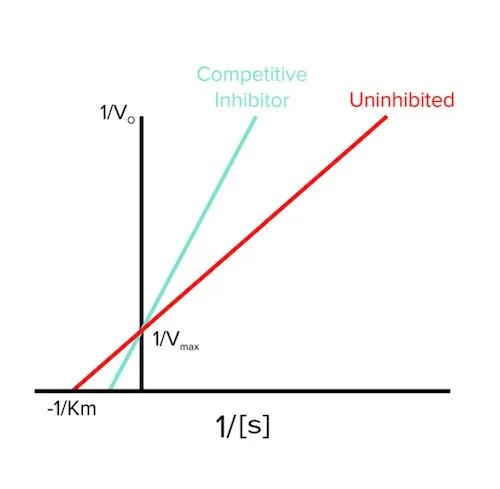

In competitive inhibition, an inhibitor binds to the enzyme’s active site, which prevents the substrate from binding. As the amount of substrate is increased, however, the effect of the inhibitor decreases, and vmax can be reached. For example, let’s say we have 1 inhibitor and 1 substrate competing for a binding site on an enzyme. There will be a battle, and we don’t know who is going to win. Now, let’s say we have 1 inhibitor and 10 substrates competing for a binding site on an enzyme. The substrates have a higher likelihood of bumping into the enzyme’s active site first since there are more of them. As we keep increasing the concentration of these substrates, the enzymes won’t notice the inhibitor is there, and vmax will stay the same as the enzymes can work at their maximum rate (answer to question 1).

Like we talked about in the last section, Km is a measure of binding affinity for the substrate and the enzyme. If the inhibitor is potentially blocking the binding site, the substrate will not be able to bind as often. Therefore, the binding affinity will become worse, so Km will increase (answer to question 2).

Finally, the Lineweaver-Burk plot will look like the following in the presence of a competitive inhibitor (answer to question 3):

Figure: competitive inhibition lineweaver burk plot

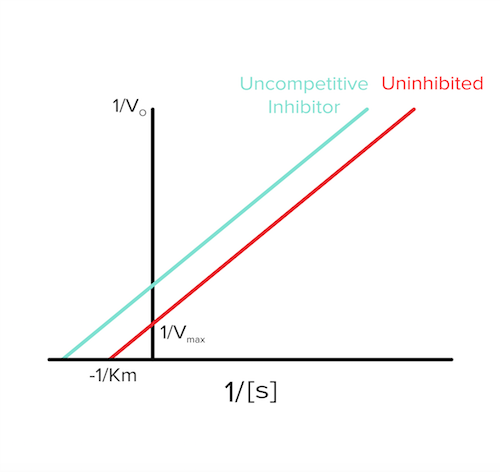

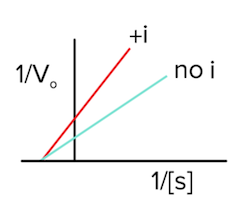

c) Uncompetitive inhibition

In uncompetitive inhibition, the inhibitor binds selectively to the enzyme-substrate (ES) complex. Now, even if we add more substrate, the enzyme will not be able to work as fast because the enzyme-substrate complex has been bound by the inhibitor. As a result, vmax will decrease (answer to question 1).

As inhibitors bind the enzyme-substrate complex, the amount of uninhibited enzyme-substrate complex decreases. This decrease in enzyme-substrate complex causes an increase in the affinity between the substrate and the enzyme as they now need to replenish the lost enzyme-substrate complex (according to Le Chatelier’s principle)! So, the increase in affinity means that Km will decrease (answer to question 2).

The Lineweaver-Burk plot will look like the following in the presence of an uncompetitive inhibitor (answer to question 3):

Figure: uncompetitive inhibition lineweaver burk plot

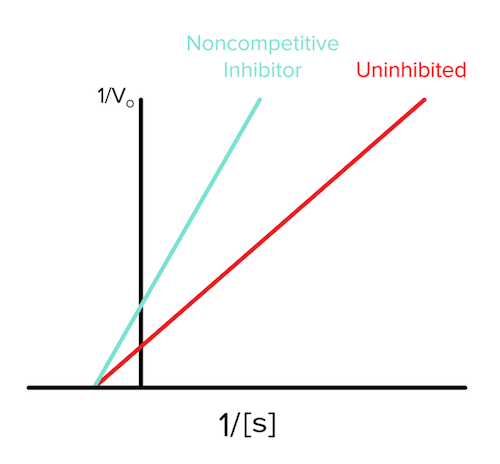

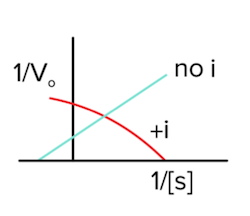

d) Mixed and noncompetitive inhibition

In mixed inhibition, the inhibitor binds to an allosteric site, or a non-active site regulatory pocket, on both the free enzyme and the enzyme-substrate complex. Many times, however, this binding is biased towards one or the other. For example, 70% of the inhibitors might bind the enzyme alone and 30% might bind the enzyme-substrate complex. As a result, mixed inhibition can be quite complicated and is not often tested on the MCAT.

There is a special case, though, in which 50% of the inhibitors bind the enzyme alone and 50% bind the enzyme-substrate complex, and this is known as noncompetitive inhibition. Again, the inhibitor is binding an allosteric site on the enzyme as with all mixed inhibitors.

Since the enzyme-substrate complex is being bound by the inhibitor, vmax must decrease, as we previously proved for uncompetitive inhibition (answer to question 1). Interestingly, since both the enzyme alone and the enzyme-substrate complex are bound with equal affinity by the inhibitor, Km will stay the same (answer to question 2).

The Lineweaver-Burk plot for noncompetitive inhibition will look like the following (answer to question 3):

Figure: noncompetitive inhibition lineweaver burk plot

This table summarizes enzymatic inhibition:

| Vmax | Km | Binding site | |

|---|---|---|---|

----

Part 4: Regulating enzyme activity

Given the importance of enzymes in our body, there are several mechanisms for regulation that we will cover in detail in this section.

a) Local environment conditions

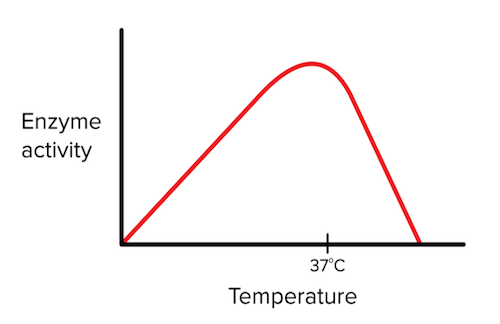

The two primary local environment conditions that affect enzyme activity are temperature and pH.

Temperature

Enzymatic activity has a love-hate relationship with temperature—we’ll explain. Up to a certain point, increasing temperature leads to an increase in the kinetic energy of enzymes and substrates. In other words, the molecules are bouncing around with a greater speed, meaning an enzyme and a substrate are more likely to encounter one another in the right orientation. However, once the temperature is too high, the enzyme will become denatured and lose its ability to catalyze the reaction.

Figure: the effect of temperature on enzyme activity

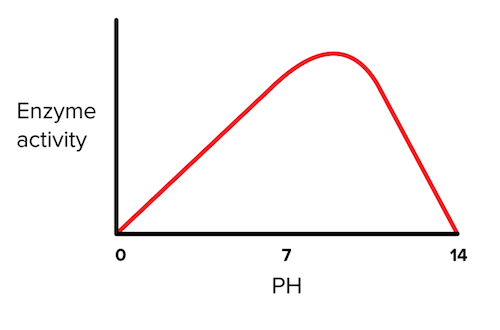

pH

Earlier in this guide, we talked about which amino acids are often found in the active site of enzymes. These amino acids include those that are charged, such as glutamic acid, aspartic acid, lysine, arginine, and histidine. Each of these amino acids has a specific pKa for their sidechain functional groups, and depending on the pH of the solution, these functional groups can be protonated or deprotonated. The protonation status is important because it can determine whether or not the enzyme can carry out its catalytic function.

Therefore, pH is extremely important for enzymes in the body as their active site residues must have the proper protonation status. Most enzymes are functional at the physiologic pH of 7.4, but stomach enzymes are the most active at a pH of 2 since the stomach must be acidic in order to carry out its function.

Figure: effect of ph on enzyme activity

b) Covalent modification

Many enzymes are regulated through post-translational modifications (PTMs) that are added to proteins. These PTMs include phosphorylation, acetylation, glycosylation, and methylation, among many others. For example, phosphorylation is important for the MAP kinase signaling pathway as each protein is activated through phosphorylation.

c) Allosteric regulation

In addition to the active site, many enzymes have allosteric sites. These are sites distant from the active site that can bind allosteric activators or allosteric inhibitors to turn the enzyme “on” or “off.”

d) Zymogens

Some enzymes are designed for highly specialized functions and are dangerous if they are not tightly controlled. Zymogens are inactive enzyme forms that must be cleaved in order to be activated. One example is trypsinogen (zymogen), which must be cleaved into trypsin in order to be active. Trypsin digests proteins, so if it was expressed in the wrong place, it would destroy entire cells and tissues.

e) Feedback regulation

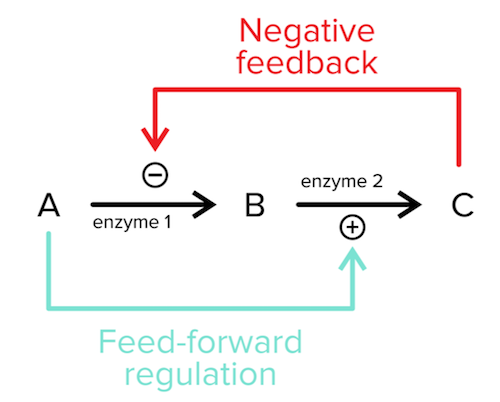

Most enzymes are involved in pathways that require careful control. Feedback regulation is how cells achieve this careful control as the production of intermediates in the pathway can regulate the enzyme’s activity. The most common form of feedback regulation is negative regulation. In negative regulation, the enzyme’s product or a product further down the pathway can inhibit the enzyme and decrease flux through the pathway. A less common form of feedback regulation is feed-forward (positive) regulation in which an enzyme’s substrate or a product upstream in the enzyme’s pathway can activate the enzyme to increase flux through the pathway.

Figure: Negative feedback and feed-forward regulation in an example biochemical pathway

f) Cooperativity

Many enzymes have multiple binding sites or form multi-domain proteins. As a result, they may bind more than one substrate, and this multiplicity can affect the enzyme’s binding affinity for multiple substrates.

Cooperativity is best understood through an example. Here, we will talk about hemoglobin—an oxygen-binding protein present in red blood cells. Each hemoglobin molecule contains four identical subunits that bind one oxygen molecule each. Interestingly, after the first hemoglobin subunit binds an oxygen substrate, the next hemoglobin subunit is much more likely to bind another oxygen substrate, and the pattern continues for the third and fourth hemoglobin subunits. As a result, hemoglobin is very efficient at capturing oxygen!

Cooperativity is often described by the Hill coefficient, which is interpreted as follows:

| Hill's coefficient | Type of cooperativity | Description |

|---|---|---|

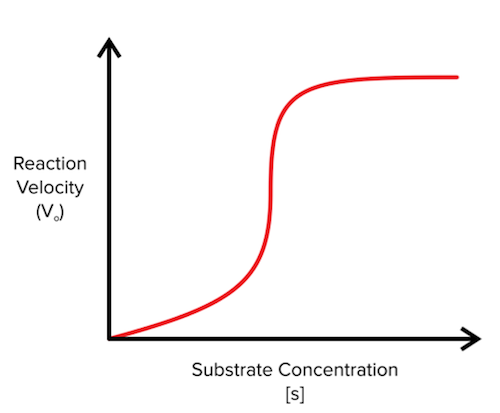

In addition to being familiar with Hill’s coefficient, you should also be able to recognize cooperativity in a graph by its signature sigmoidal shape (it looks like an S):

Figure: Reaction velocity versus substrate concentration for a positively cooperative enzyme

----

Part 5: High-yield terms

Catalyst: a substance that speeds up the rate of a reaction without being consumed itself

Biological catalyst: a molecule (can be protein or nucleic acid) that speeds up the rate of a biochemical reaction without being consumed itself

Activation energy: the input energy required to initiate a chemical reaction

Kinetics: how quickly a reaction converts reactants to products

Reaction rate: the rate at which reactants are consumed OR the rate at which products are formed

Regeneration: the ability of enzymes to reform and engage in multiple catalytic cycles

Lock-and-key model: an enzyme-substrate binding theory that poses the substrate as a “key” that fits perfectly into the enzymatic “lock” without changing conformations

Induced fit model: an enzyme-substrate binding theory that poses the substrate and enzyme undergo slight conformational changes upon binding to one another

One-letter amino acid code: a one-letter code that defines an amino acid (e.g., K is lysine)

Three-letter amino acid code: a three-letter code that defines an amino acid (e.g., Lys is lysine)

Michaelis-Menten: a plot that measures reaction velocity versus an increasing concentration of substrate while holding the enzyme concentration constant

Reaction velocity: the speed at which a certain concentration of enzymes convert substrate to product

Vmax: the maximum speed at which a certain concentration of enzymes can convert substrate to product

Km: the substrate concentration at ½ vmax and also corresponds to affinity between the enzyme and substrate

Saturation: the point at which additional substrate does not produce an increase in reaction velocity because the enzymes are already working as fast as they can

Catalytic efficiency: describes the efficiency of an enzyme by incorporating how fast the enzyme is working (kcat) and how well the enzyme can bind substrate (Km) using the following expression: kcat / Km

Lineweaver-Burk: a double reciprocal of the Michaelis-Menten plot in which (1/reaction velocity) is plotted against 1/[S]

Competitive inhibition: an inhibitor competes with substrate binding to the active site, resulting in an unchanged vmax and an increased Km

Uncompetitive inhibition: an inhibitor binds to the enzyme-substrate complex, resulting in a decreased vmax and a decreased Km

Mixed inhibition: an inhibitor binds to both the enzyme alone and the enzyme-substrate complex, resulting in a decreased vmax and an increased or decreased Km

Noncompetitive inhibition: a subclass of mixed inhibition in which an inhibitor binds to the enzyme alone 50% of the time and the enzyme-substrate complex 50% of the time, resulting in a decreased vmax and an unchanged Km

Cofactor/coenzyme: binds to the enzyme’s active site and assists in catalyzing the reaction

Prosthetic group: a cofactor or coenzyme that binds extremely tightly to the enzyme

Holoenzyme: an enzyme with its cofactors and/or coenzymes

Apoenzyme: an enzyme without its cofactors and/or coenzymes

Post-translational modification: the covalent addition of a functional group or atom to an enzyme

Allosteric sites: a site distant from the active site that can be used as a point of regulation

Allosteric activators: binds to an enzyme’s allosteric site and activates the enzyme

Allosteric inhibitors: binds to an enzyme’s allosteric site and inhibits the enzyme

Zymogens: inactive enzyme forms that must be cleaved in order to be activated

Feedback regulation: the control of flux through biological pathways by using positive and negative regulation

Negative regulation: the enzyme’s product or a product further down the pathway can inhibit the enzyme and decrease flux through the pathway

Feed-forward (positive) regulation: an enzyme’s substrate or a product upstream in the enzyme’s pathway can activate the enzyme to increase flux through the pathway

Cooperativity: the binding of substrate to a multi-subunit protein affects the binding of subsequent substrates

Hill’s coefficient: a term that describes whether a multi-subunit protein is not cooperative (=1), positively cooperative (>1), or negatively cooperative (<1)

Sigmoidal: an S-shaped curve that is characteristic of cooperative behavior

Looking for MCAT Practice Questions? Check out our proprietary MCAT Question Bank for 4000+ sample questions and eight practice tests covering every MCAT category.

Gain instant access to 4,000+ representative MCAT questions across all four sections to identify your weaknesses, bolster your strengths, and maximize your score. Subscribe today to lock in the current investments, which will be increasing in the future for new subscribers.

----

Part 6: Enzymes practice passage

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are commonly used in the treatment of high blood pressure and heart failure. By inhibiting ACE, the production of angiotensin II decreases and blood vessels widen to decrease blood pressure and strain on the vascular system. The inhibition of ACE via synthetic inhibitors, however, produces various unwanted side effects. As a result, researchers want to develop a natural ACE inhibitor.

In a new study, scientists aim to purify and introduce natural ACE inhibitors extracted from Ziziphus jujuba fruits. First, proteins from Ziziphus jujuba were lysed by trypsin, papain, and a combination of the two. Then, acquired peptide fragments from the digestion were purified via chromatography and assayed for ACE inhibitory activity. Peptide fractions containing inhibitory activity were sequenced using tandem mass spectrometry. Finally, to elucidate the mode of peptide binding to ACE, homology modeling, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations were performed.

The amino acid sequences of three-amino acid long F2 and F4 peptides, which were the most active hydrolysates, were determined to be IER and IGK with the IC50 values of 0.060 and 0.072mg/ml, respectively. Peptides F84 and F72 were determined to be AAA and III, respectively. Of the 234 screened peptides, only F2 and F4 showed an inhibitory effect on ACE, so the researchers decided to investigate the kinetics of inhibition.

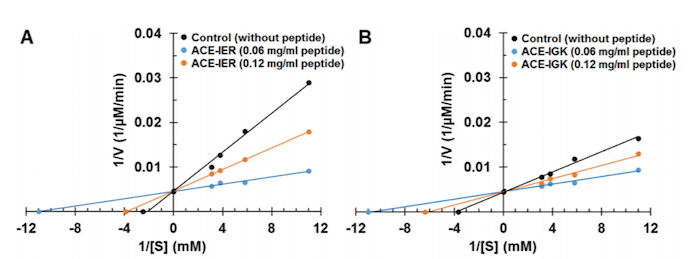

The F2 and F4 peptides were added at increasing concentrations to a constant concentration of ACE enzyme. ACE activity was assayed, and the results were plotted as a Lineweaver-Burk plot (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Lineweaver-Burk plots for IER and IGK treatments of ACE.

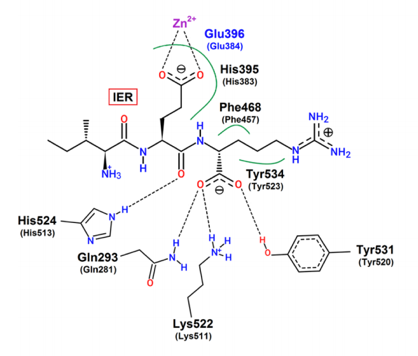

Researchers then performed structural analysis of the IER tripeptide bound to the enzyme’s active site. They found that the IER peptide binds close to the zinc binding site, and binding occurs through hydrogen bonding with Gln293, Lys522, His524, Tyr531 in addition to several hydrophobic interactions (Figure 2).

Creator and Attribution party: Memarpoor-Yazdi, M., Zare-Zardini, H., Mogharrab, N. et al. Purification, Characterization and Mechanistic Evaluation of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Peptides Derived from Zizyphus Jujuba Fruit. Sci Rep 10, 3976 (2020). The article’s full text is available here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-60972-w. The article is not copyrighted by Shemmassian Academic Consulting. Disclaimer: Shemmassian Academic Consulting does not own the passage presented here. Creative common license: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Changes were made to original article to create an MCAT-style passage.

Question 1: Which of the following peptides is MOST likely to bind to a phosphate-coated column?

A) F2

B) F4

C) F72

D) F84

Question 2: Which of the following best describes how trypsin activity is regulated?

A) It is sequestered in specific organelles.

B) It is secreted as an inactive zymogen before cleavage into the active product.

C) It is only expressed for short periods during the S-phase of the cell cycle.

D) It is bound by two allosteric inhibitors that prevent it from being active in incorrect locations.

Question 3: According to the passage, researchers found that the IER peptide binds close to the zinc binding site near the active site of the enzyme. Which of the following best describes the role of zinc in the enzyme?

A) Coenzyme

B) Apoenzyme

C) Cofactor

D) Catalytic residue

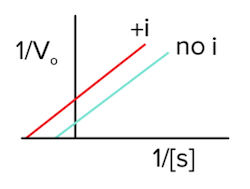

Question 4: The researchers use a new peptide that is known to be an uncompetitive inhibitor. Which of the following Lineweaver-Burk plots are the researchers MOST likely to observe?

A)

B)

C)

D)

Question 5: Researchers are testing the kinetics of a novel enzyme inhibitor. After assessing Michaelis-Menten kinetics, they conclude that the inhibitor binds to both the enzyme alone and the enzyme-substrate complex, though it binds to the enzyme alone with a slightly higher affinity. This is an example of:

A) Competitive inhibition

B) Noncompetitive inhibition

C) Uncompetitive inhibition

D) Mixed inhibition

Answer key for passage-based questions

Answer choice B is correct. Peptide F4 has the sequence IGK, according to the passage. Therefore, the charge is 0 + 0 + 1, and the positive charge would be likely to bind the negatively charged phosphate on the column. Peptide F2 has the sequence IER, which carries the charge 0 -1 + 1, for a net charge of 0 (choice A is incorrect). Peptide F72 has the sequence III and peptide F84 has the sequence AAA, both of which are neutrally charged as they are 0 + 0 + 0 (choices C and D are incorrect).

Answer choice B is correct. Trypsin is a zymogen, meaning its inactive form (trypsinogen) must be cleaved in order to generate the active enzyme (trypsin). Trypsin is not sequestered in specific organelles (choice A is incorrect), expressed during only the S-phase (choice C is incorrect), or bound by allosteric inhibitors (choice D is incorrect).

Answer choice C is correct. Zinc is a cofactor, or ion that assists with catalysis, commonly found in enzymes. A coenzyme assists an enzyme with catalysis, but it is a protein (choice A is incorrect). An apoenzyme is a protein without its cofactors or coenzymes (choice B is incorrect). A catalytic residue is an amino acid, not a zinc ion (choice D is incorrect).

Answer choice D is correct. Uncompetitive inhibitors decrease both the vmax and the Km, causing the y-intercept (1/vmax) to become more positive and the x-intercept (-1/Km) to become more negative. The easier way to recognize an uncompetitive inhibitor is that the Lineweaver-Burk plot will be parallel and shifted up.

Answer choice D is correct. Mixed inhibition occurs when an inhibitor binds both the enzyme alone and the enzyme-substrate complex. In this case, the inhibitor may bind the enzyme alone 60% of the time while binding the enzyme-substrate complex 40% of the time. Competitive inhibition occurs when an inhibitor binds the active site of an enzyme (choice A is incorrect). Noncompetitive inhibition is a subclass of mixed inhibition that describes an inhibitor binding an allosteric site, and this type of inhibitor binds the enzyme alone and enzyme-substrate complex with equal affinity (choice B is incorrect). Uncompetitive inhibition occurs when an inhibitor binds the enzyme-substrate complex alone (choice C is incorrect).

----

Part 7: Enzymes practice questions

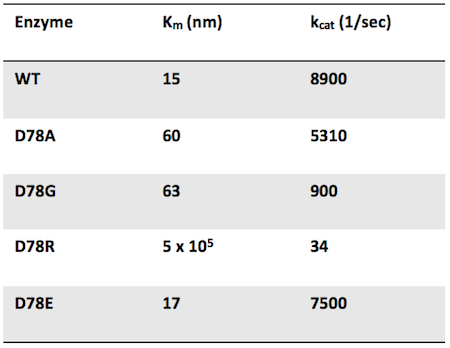

Question 1: Researchers mutate the active site aspartate of an enzyme to four different amino acids. The mutant enzymes have the following properties:

Which mutant has the highest catalytic efficiency?

A) D78A

B) D78G

C) D78R

D) D78E

Question 2: What type of enzyme adds a phosphate group to a protein substrate?

A) Dehydrogenase

B) Lyase

C) Transferase

D) Carboxylase

Question 3: Compound X is an uncompetitive inhibitor of Enzyme A. What effects would the addition of Compound X have on the kinetics of Enzyme A, assuming Michaelis-Menten kinetics?

A) Vmax decreases, Km unchanged

B) Vmax decreases, Km increases

C) Vmax increases, Km decreases

D) Vmax decreases, Km decreases

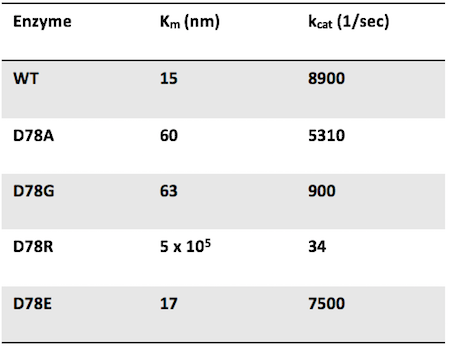

Question 4: Researchers mutate the active site aspartate of an enzyme to four different amino acids. The mutant enzymes have the following properties:

Which of the following provides the best explanation for the low catalytic efficiency of the D78R mutant?

A) Disruption of hydrophobic effect

B) Change in charge of a key active site residue

C) Disulfide bridge disruption

D) Reduction in size of an active site residue

Question 5: Which of the following types of enzymatic inhibition is a subclass of mixed inhibition?

A) Competitive

B) Uncompetitive

C) Noncompetitive

D) Traditional

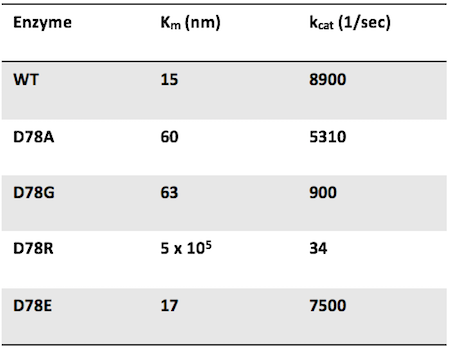

Question 6: Researchers mutate the active site aspartate of an enzyme to four different amino acids. The mutant enzymes have the following properties:

Which mutant has the lowest catalytic efficiency?

A) D78A

B) D78G

C) D78R

D) D78E

Question 7: Where is an enzyme with an observed maximal activity at a pH of 2 most likely to be found?

A) Brain

B) Kidney

C) Stomach

D) Liver

Answer key for standalone practice questions

Answer choice D is correct. Catalytic efficiency is defined by kcat (the catalytic activity of one enzyme) divided by Km. WT has the highest catalytic efficiency since there is no active site mutation. The mutant with the highest catalytic efficiency would have the highest kcat and the lowest Km. This combination is satisfied by the D78E mutation (choice D is correct). This mutation also makes sense as least likely to affect enzyme activity due to the maintenance of a negative charge in the active site through the aspartate to glutamate mutation.

Answer choice C is correct. Kinases add phosphate groups to a protein substrate, and kinases are a subclass of transferases. A dehydrogenase removes hydrogen atoms (choice A is incorrect), a lyase cleaves a biomolecule without water (choice B is incorrect), and a carboxylase adds a carboxyl group to a biomolecule (choice D is incorrect).

Answer choice D is correct. Uncompetitive inhibitors bind the E-S (enzyme-substrate complex), thereby disrupting the activity of the enzyme and leading to a decrease in Vmax. (choice C is incorrect). Based on Le Chatelier’s principle, the amount of E-S complex appears to decrease, forcing the E + S → ES reaction scheme to the right. S decreases, and Km is a measure of substrate concentration. Therefore, Km decreases (choice D is correct; choices A and B are incorrect).

Answer choice B is correct. Changing the charge of an important active site residue is likely to alter the enzyme’s mechanism, thereby leading to a decrease in catalytic efficiency.

Answer choice C is correct. Noncompetitive inhibition is a subclass of mixed inhibition in which the inhibition binds the enzyme alone and the enzyme-substrate complex with equal affinity (choice C is correct). Competitive and uncompetitive inhibition are classes of their own (choices A and B are incorrect). Traditional inhibition is made up (choice D is incorrect).

Answer choice C is correct. Catalytic efficiency is defined by kcat (the catalytic activity of one enzyme) divided by Km. WT has the highest catalytic efficiency since there is no active site mutation. The mutant with the highest catalytic efficiency would have a high kcat and a low Km. Therefore, the mutation with the lowest catalytic efficiency would have a low kcat and a high Km. D78R satisfies this condition. Additionally, it makes sense that changing an active site residue from being negatively charged to positively charged would have a bad effect on enzymatic efficiency!

Answer choice C is correct. An enzyme with maximal activity at a pH of 2 is most likely to be found in the stomach since the stomach utilizes an acidic environment to aid in the breakdown of food. Enzymes found in the brain, kidney, and liver are more likely to function around the normal physiological pH of around 7.4 (choices A, B, and D are incorrect).