MCAT Psychology Practice Questions

/Boost your MCAT Psychology performance with curated practice problems and detailed guidance on important concepts and exam strategies.

(Note: This resource also appears in our MCAT Ultimate Guide.)

----

Introduction

MCAT Psychology Practice Passage #1

MCAT Psychology Practice Passage #2

MCAT Psychology Practice Passage #3

MCAT Psychology Practice Questions (Standalone)

----

Introduction

Psychology makes up 65% of the MCAT psychology/sociology section. Many premeds don’t realize that psychology makes up over 16% of their overall MCAT score. That 16% might be the difference between an application that receives “We are pleased to inform you” versus “We regret to inform you” given the importance of the MCAT in medical school admissions.

The MCAT is a long exam, and the psychology/sociology section is the last section you’ll take on the MCAT. As a result, by the time psych/soc rolls around, many premeds begin to tire, their eyelids become heavy, and the words on the computer screen seem to blend together. A solid MCAT study schedule will help you slate in enough practice so that you can endure the exam come test day.

Many students think that they can ace MCAT psychology questions by memorizing the definition of every vocabulary word in every content book. While it is true that this will increase your score, you’ll need a mastery of each word to ace MCAT psychology questions. In addition to the definition of each word, you should know an example of the term and be able to recognize and apply the vocab word in new contexts.

(Suggested Reading: MCAT Psychology/Sociology: Everything You Need to Know)

So, how do you improve your performance on the MCAT psychology/sociology section? In addition to vocab and content knowledge, the simple answer is practice! Here, we’ll test your psychology knowledge using MCAT-style passages. Use the following three psychology passages and five standalone questions to test your knowledge. Each explanation for the passage-based questions will have suggestions for what you should review if you miss a question. Good luck!

----

MCAT Psychology Practice Passage #1

Recent studies have shown that television can adversely impact cognitive processes in both children and young adults. In previous studies, researchers found that in individuals ages 6-23, higher than average amounts of television watching lead to an 8-14% decrease in the ability of participants to quickly and correctly solve math problems. In addition, participants were less likely to recall list items or accurately identify emotions on a confederate during an in-person experiment.

A group of researchers is specifically interested in studying the effect of television on memory. The researchers recruit at least fifty participants in each of the following age groups: 6-8, 9-11, 12-14, and 15-17. Each of the participants watches 15 hours of TV per week as confirmed by the participants themselves and a guardian. The participants watch a range of television programming throughout the week.

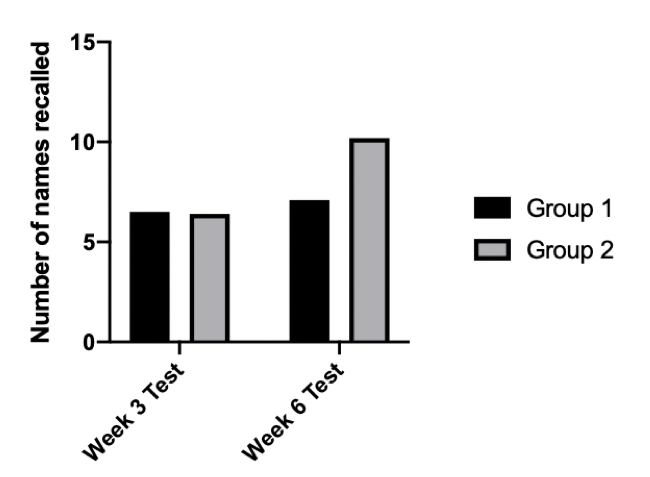

To conduct the experiment, the researchers split up the participants in each age group into Group 1 or Group 2. The Group 1 participants watch 15 hours of TV a week for three consecutive weeks (weeks 1-3). At the end of the third week, the participants are brought into a testing center and given a list of 20 names. Ten minutes later, they are asked to recall as many names as possible. The Group 1 participants then watch 15 hours of TV a week for the next three consecutive weeks (weeks 4-6) and repeat the memory assessment. Group 2 participants follow an identical plan as Group 1 participants for weeks 1 through 3. However, during weeks 4 through 6, Group 2 participants are not allowed to watch any TV during the week. Group 2 participants complete the same memory test as group one students at the end of week 3 and the end of week 6. The results from the experiment are shown in Figure 1 for the 9 to 11-year-old age group.

Figure 1: Memory test performance for 9 to 11-year-old age group.

Note: The information in this passage was created for the sole purpose of presenting an MCAT-style passage and should not be construed to be factually true.

1. In a follow-up study, researchers found that participants are best able to recall names at the end of the list better than names at the beginning of the list. This is known as:

A) Recency effect

B) Proactive interference

C) Primacy effect

D) Retroactive interference

2. Which of the following do the researchers NOT account for in the study?

A) Intergroup variability

B) Amount of TV watched

C) Genre of TV watched

D) Age

3. Which of the following conclusions is NOT supported by the results shown in Figure 1?

A) Group 1 and 2 participants recall a similar number of names when they watch 15 hours of TV a week.

B) Retroactive interference prevents Group 1 participants from performing as well as Group 2 participants on the week 6 test.

C) The ability of Group 2 participants to recall names improved on the week 6 test.

D) The number of names recalled by participants is associated with time spent watching TV.

4. Which of the following best describes the type of study described in the passage?

A) Observational study

B) Experimental study

C) Case study

D) Survey study

MCAT psychology practice passage #1 answers and explanations

1. Answer choice A is correct. The recency effect causes participants to recall names at the end of the list (choice A is correct). Proactive interference describes past memories interfering with new memories (choice B is incorrect). The primacy effect would cause participants to remember words earlier in the list (choice C is incorrect). Retroactive interference describes new memories interfering with the recall of past memories (choice D is incorrect).

Review recency effect, primacy effect, proactive interference, and retroactive interference.

2. Answer choice C is correct. The passage indicates that “the participants watch a range of television programming throughout the week,” meaning the researchers do not control for TV genre (choice C is correct). Intergroup variability is controlled by Group 2 watching TV for weeks 1-3 as the researchers can verify that recall between Groups 1 and 2 is the same after those three weeks (choice A is incorrect). The amount of TV watched is controlled for as participants in the TV-watching condition must watch 15 hours of TV (choice B is incorrect). Age is controlled for as the participants are split into smaller age bins (choice D is incorrect).

Review the text, experimental goals, and experimental setup.

3. Answer choice B is correct. While it is true that Group 1 participants do not perform as well as Group 2 participants on the week 6 test, there is not enough information in Figure 1 to conclude that retroactive interference, which describes new memories interfering with the recall of past memories, led to the weaker performance (choice B is correct). The week 3 test results demonstrate that Group 1 and 2 participants do recall a similar number of names when they watch 15 hours of TV a week (choice A is incorrect). The week 6 test shows that Group 2 participants did improve when they stopped watching TV (choices C and D are incorrect).

Review TAID P method of figure analysis.

4. Answer choice B is correct. Since the researchers are actively manipulating an independent variable (number of hours of TV watched) and measuring a dependent variable, this is an experimental study (choice B is correct). An observational study involves observation without manipulation or intervention (choice A is incorrect). A case study looks at only an individual or a very small number of participants (choice C is incorrect). A survey study involves the distribution of a survey and analysis of results (choice D is incorrect).

Review experimental methods in psychology.

Gain instant access to the most digestible and comprehensive MCAT content resources available. 60+ guides covering every content area. Subscribe today to lock in the current investments, which will be increasing in the future for new subscribers.