DNA for the MCAT: Everything You Need to Know

/Master MCAT DNA concepts with high-yield content, targeted practice questions, and detailed answers to boost your understanding and improve your score.

(Note: This guide is part of our MCAT Biochemistry series.)

Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: Structure of DNA

a) Nitrogenous bases

b) Phosphate backbone

c) G-C content

d) DNA synthesis

Part 3: The Central Dogma

a) Transcription

b) Translation

c) Exceptions to the central dogma

Part 4: Epigenetics and imprinting

a) Histone structure and function

b) X inactivation

Part 5: Disorders and cancers

a) Oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes

b) Chromosomal defects

Part 6: High-yield terms

Part 7: Passage-based questions and answers

Part 8: Standalone questions and answers

----

Part 1: Introduction

Understanding DNA and its function is crucial on the MCAT, especially as DNA is the biological basis of life. DNA, or deoxyribonucleic acid, is one of the two main molecules of nucleic acids (the other being RNA, or ribonucleic acid). DNA stores and selectively expresses the genetic information our cells need to function. DNA is carefully replicated and inherited from one generation of cells to the next to avoid any errors. Errors in DNA replication can vary significantly, from unnoticeable mutations to life-threatening illnesses, such as cancer. As a result, proper DNA regulation is vital to cell survival.

This guide will take a tour through the structure and function of DNA and what can go wrong. When studying DNA, it’s easy to confuse the names of the bases and building blocks of DNA as well as the different modifications DNA undergoes in the cell. It’s helpful to create a list outlining why each component or modification of DNA is necessary for its function. Throughout this guide, you will also see bolded terms that will be important to recall on the exam.

Let’s dive in!

----

Part 2: Structure of DNA

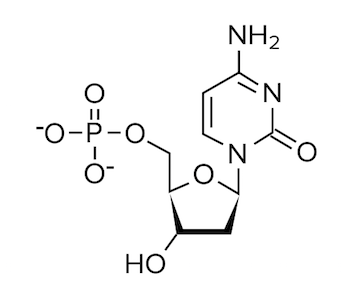

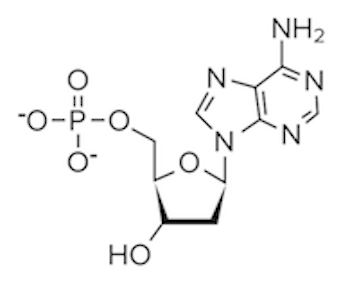

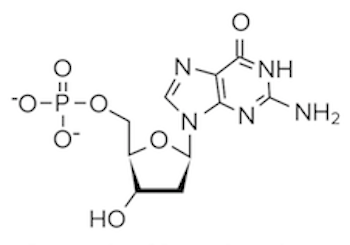

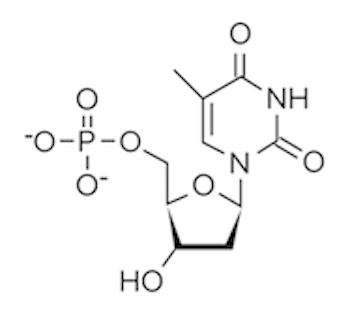

Let’s take a close look at the structure of DNA. DNA exists as a double helix—an identifying structure that is unique to this biomolecule. In a double helix, two strands of DNA wrap around each other and form a twisted ladder pattern. There are two important parts of a DNA molecule: the nucleotides and the sugar phosphate backbone. Four unique nucleotides that bond with each other to create the rungs of the ladder: adenosine monophosphate (adenine), guanosine monophosphate (guanine), cytidine monophosphate (cytosine), and deoxythymidine monophosphate (thymine). Each nucleotide has a unique structure shown below.

Figure: Nucleotide bases used in the structure of DNA

What do each of these four nucleotides have in common? All of the bases have a very similar structure. Each nucleotide consists of a phosphate group (PO4-), a nitrogenous base, and a pentose sugar that links the other two groups together. In contrast, nucleosides are molecules that only consist of a nitrogenous base and a pentose sugar.

a) Nitrogenous bases

The nucleotides have different nitrogenous bases. There are two classes of nitrogenous bases: purines and pyrimidines. While both purines and pyrimidines are aromatic nitrogenous bases, they differ in size and ring structure. Purines are made of two rings and are larger than pyrimidines, which contain only one ring.

Take a close look at the structure of nitrogenous bases of the nucleotides. Adenine and guanine have purine bases, while cytosine and thymine have pyrimidine bases. Adenine and guanine are often broadly classified as purine nucleotides, while cytosine and thymine are classified as pyrimidine nucleotides. It’s important to remember adenine and guanine still have differences in the organic structure: for instance, in the number of attached carbonyl (C=O) bonds and where they are located. The same goes for cytosine and thymine. Memorizing each nucleotide’s structure will be crucial for test day.

Each nucleotide follows strict rules for bonding with other nucleotides. In DNA, purine bases bond with pyrimidine bases instead of other purines, and vice versa. In particular, guanine and cytosine almost exclusively bond together while adenine and thymine bond with each other. This bonding is known as Watson-Crick base pairing. Scientists have discovered exceptions to these rules, but you won’t be tested on them.

When guanine and cytosine bond, three hydrogen bonds form. When adenine and thymine bond, two hydrogen bonds form. We’ve illustrated these bonds below.

Figure: Hydrogen bonds provide stability between bonded bases and prevent rotation of bonded nucleotides.

These hydrogen bonds provide stability to the DNA, making the guanine and cytosine pair and adenine and thymine pair favorable. An easy way to remember which nucleotides bond together is by memorizing the letters AT and GC together. This will remind you that adenine (A) bonds with thymine (T), while guanine (G) bonds with cytosine (C).

b) Phosphate backbone

Imagine having a ladder with only rungs. It wouldn’t function as a ladder at all! A ladder needs its side rails to work. Similarly, DNA needs a backbone to hold the double helix structure together.

The DNA backbone is known as a sugar phosphate backbone. The sugar phosphate backbone consists of a repeating pattern of sugar and phosphate groups bonded together.

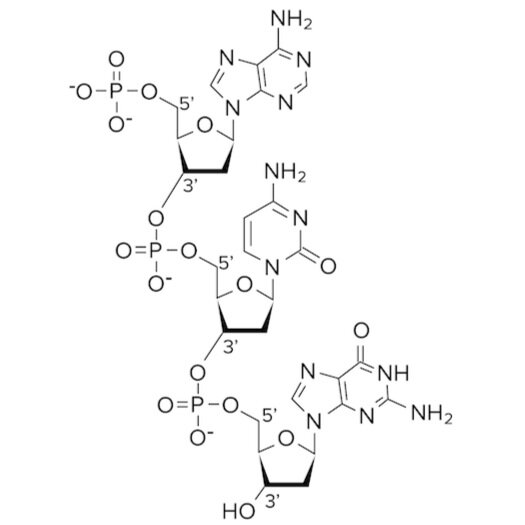

Recall the structure of a nucleotide and that each nucleotide base contains a phosphate group and pentose sugar. The phosphate group is attached to the 5’ carbon of the pentose sugar. In the sugar phosphate backbone, the phosphate group of one nucleotide creates a phosphodiester bond with the 3’ carbon of the pentose sugar on the adjacent nucleotide. Try to trace the locations of the phosphodiester bond on the diagram below.

Figure: Phosphodiester bonds in the sugar phosphate backbone.

Phosphodiester bonds exist between adjacent nucleotides to create the backbone of DNA. An important fact to know about DNA is that its backbone is negatively charged. Can you see why? The backbone is negatively charged because the phosphate groups carry charged oxygen atoms. This negatively charged backbone creates an attractive force between the aqueous, polar environment and the DNA molecule.

Consider what might happen if the negatively charged backbone were on the interior of the molecule and the aromatic bases were on the exterior of the molecule. This would lead to a very unfavorable energy conformation—the two negative charges on either side of the backbone would repel each other, and the aromatic bases would not be soluble in water at all!

c) G-C content

One of the most important ways to analyze the nucleotide composition of DNA is to calculate its G-C content. G-C content is a measure of the percentage of nucleotide bases that contain guanine or cytosine in a fragment of DNA. Why might this percentage be important?

Recall from our discussion of guanine and cytosine bonds that G-C bonds are more stable than A-T bonds. When guanine and cytosine bond, three strong hydrogen bonds are created. Breaking a single hydrogen bond takes a significant amount of energy, let alone three.

G-C content is important because it determines the melting point of DNA, as well as its accessibility by polymerases. A higher G-C content means that there are a greater number of guanine-cytosine base pairs holding the two DNA strands together. This means there are also more hydrogen bonds. A greater amount of energy is needed to dissociate the two strands, leading to a higher melting point. A lower G-C content means the opposite. Less energy is needed to dissociate the DNA strands, lowering the melting point and making the DNA more accessible to polymerases.

The MCAT may ask you to calculate nucleotide composition using Chargaff’s rules. Chargaff’s rules state that the ratio of purine nucleotides to pyrimidine nucleotides in DNA is 1-to-1. In fact, the ratio of guanine nucleotides to cytosine nucleotides and the ratio of adenine nucleotides to thymine nucleotides are also each 1-to-1.

Chargaff’s rules hold true for any piece of DNA we come across. Why? Recall that adenine and thymine bond together while guanine and cytosine bond together. Since these bases always bond in this pattern—and DNA consists of only bonded nucleotides—there must be a 1-to-1 ratio of adenine to thymine and guanine to cytosine. To understand the first part of Chargaff’s rules, let’s look at an example.

Consider the DNA strand pictured below. If we count the number of purine and pyrimidine nucleotides, we get a 1 to 1 ratio. If we count all of the nucleotides, we get a 1-to-1 ratio of guanine to cytosine and a 1-to-1 ratio of adenine to thymine.

Figure: Every DNA strand follows Chargaff’s rules.

Now, let’s imagine a fragment of DNA had a G-C content of 30%. The low G-C content tells us that this piece of DNA has a low melting point and is more accessible to polymerases. Chargaff’s rules allow us to determine that the DNA must be 15% guanine and 15% cytosine.

We also know that the rest of the nucleotide content in the DNA must be composed of adenine and thymine (since DNA has two types of nucleotide bonds). Thus, the percentage of combined adenine and thymine content must be 70%, or 35% each.

We now know our DNA fragment consists of 15% guanine, 15% cytosine, 35% adenine, and 35% thymine. If we add the percentages of the purine nucleotides together and pyrimidine nucleotides together like in Chargaff’s rule, we get 50% purine content and 50% pyrimidine content: resulting in a 1-to-1 ratio, just as Chargaff described.

Gain instant access to the most digestible and comprehensive MCAT content resources available. 60+ guides covering every content area. Subscribe today to lock in the current investments, which will be increasing in the future for new subscribers.

d) DNA synthesis

As cells grow and divide, they also need to replicate their DNA. How are they able to exactly duplicate these lengthy sequences of nucleotide bases?

First, we need to understand the directionality of DNA. Each end of DNA is assigned a number, 5’ or 3’, based on the orientation of pentose sugar in the nucleotides. The 5’ end of DNA refers to the end of the backbone chain where the phosphate group is bound to the 5’ carbon of the pentose sugar. The 3’ end of DNA refers to the end where the 3’ carbon creates a phosphodiester bond with the adjacent nucleotide.

When DNA bonds together, the two strands run in opposite directions or (antiparallel). One strand of DNA runs in the 5’ to 3’ direction, while its complement runs in the 3’ to 5’ direction. (It may be helpful to refer to the previous image to see how this fits together.)

Duplicating DNA requires that the helix “unzip” momentarily so its nucleotides can be read. Because single-stranded DNA is unstable and prone to degradation by DNA nucleases, DNA unzips in small intervals. DNA replication starts at the origin of replication, a sequence rich in adenine-thymine bonds. Chromosomes of eukaryotic organisms may have multiple origins of replication, thus allowing replication to occur simultaneously at multiple different sites.

Two important enzymes, helicase and DNA topoisomerase, begin to unzip the DNA and relax the coiling in the DNA, respectively. (As DNA is unwound, it can form tangles known as supercoils. Topoisomerases help to unwind the tangled coils that begin to form by making selective cuts in the phosphate backbone and repairing them.) The unzipping progresses in both directions away from the origin of replication, so replication can progress in both directions and decrease the amount of time needed.

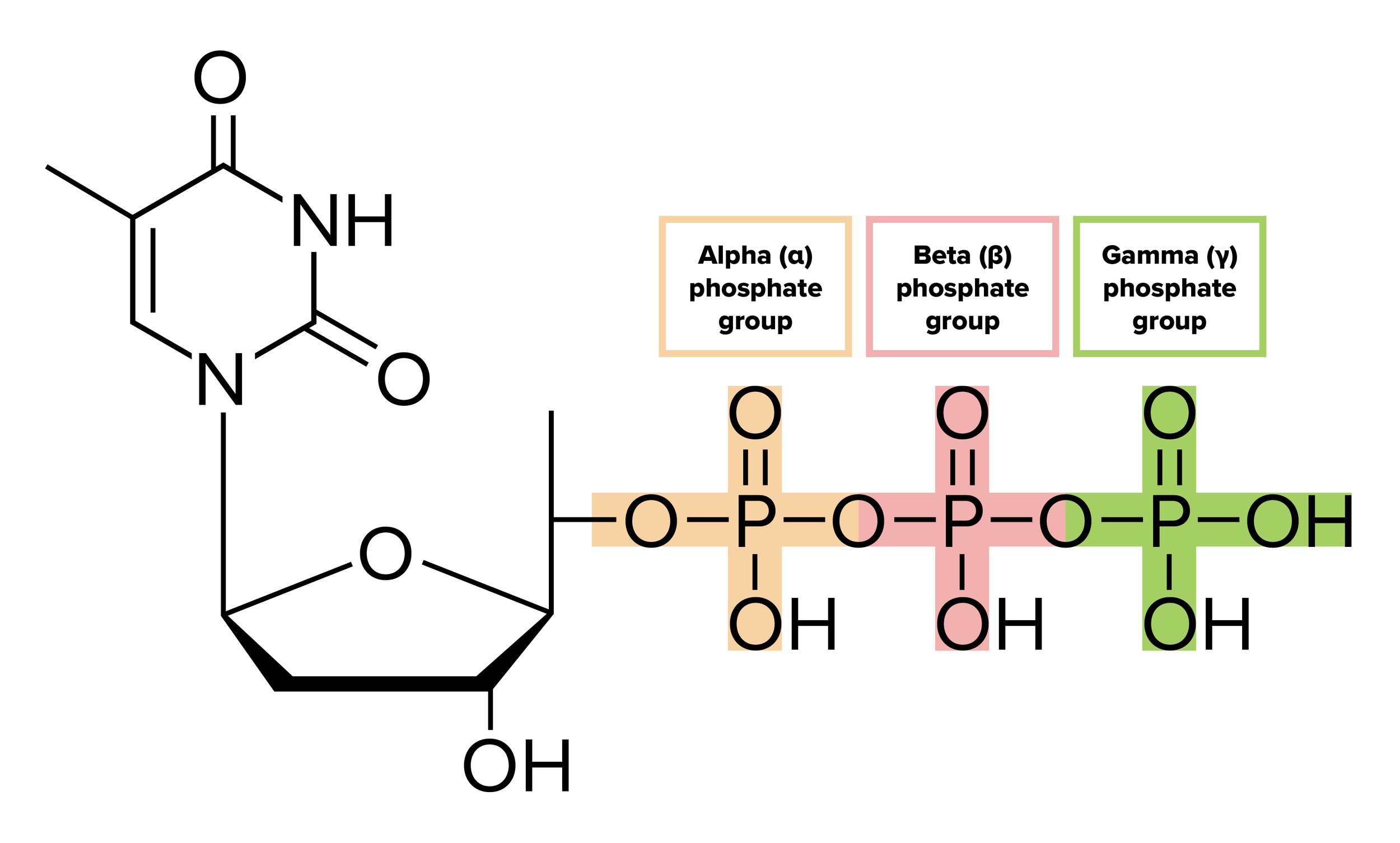

DNA polymerase (sometimes called DNA pol) can continuously add nucleotides triphosphates to create a new daughter strand. It’s important to note that the nucleotides added by DNA polymerase are in the form of nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs). Each phosphate group is designated alpha (α), beta (β), or gamma (γ) depending on its distance from the nucleoside. When a nucleotide is incorporated into the growing DNA strand, the β and γ phosphate groups are cleaved off, releasing the energy that drives the formation of the phosphodiester bond. In fact, when we think of all the instances where a high-energy triphosphate like ATP is hydrolyzed to fuel a reaction, it is generally the γ phosphate group that is cleaved off, leaving behind ADP!

Figure: Deoxythymidine Triphosphate, the nucleotide form of thymine prior to its addition by DNA polymerase. The beta and gamma phosphates are cleaved during this addition.

DNA polymerase creates a translated strand that is complementary. The translated (or new) strand will contain an adenine base (A) at every position there is a thymine base (T) in the DNA sequence, a guanine base (G) at every position there is a cytosine base (C) in the DNA sequence, and vice versa.

DNA polymerase synthesizes DNA but with a catch. The polymerase only creates DNA in a 5’ to 3’ fashion. That means the template strand the polymerase is attached to must run in the 3’ to 5’ direction. While this is the case for one of the strands (called the leading strand), recall that the two strands of DNA are antiparallel—so the other one (called the lagging strand) runs in the 5’ to 3’ direction.

DNA replication of the leading parent strand runs smoothly. Replication of the lagging parent strand is discontinuous. Because DNA polymerase only runs in the 5’ to 3’ direction, DNA primase continuously adds new primers along the lagging strand. DNA polymerase uses these primers to create short sequences of DNA known as Okazaki fragments. At the end, DNA ligase seals the fragments together and fills in any gaps that may have been left behind to create a new daughter strand.

Figure: DNA replication.

DNA is replicated in a semiconservative manner. This means that during replication, each strand acts as a template, or parent strand, for a new DNA molecule. After one round of DNA replication and mitosis, each daughter cell contains one new DNA molecule composed of one strand of original DNA (from the parent cell) and one newly synthesized strand of DNA.

When DNA is being replicated, DNA polymerase also proofreads the new daughter strand being synthesized. The polymerase will ensure that the complementary nucleotide is paired to the correct nucleotide on the parent strand of DNA.

Many of the mistakes that DNA polymerase makes are quickly resolved through proofreading. For mistakes that aren’t caught during proofreading, the cell relies on mismatch repair. Mismatch repair occurs in the G2 phase of the cell cycle to correct any leftover errors from synthesis. Enzymes such as MSH2 and MLH1 are responsible for detecting, removing, and replacing incorrectly paired nucleotides.

As the replication of DNA is repeated multiple times, the ends of the DNA molecules become shorter and shorter. These are regions known as telomeres. Telomeres protect and stabilize the coding regions of DNA. As telomeres shorten, they eventually reach the shortest allowable length, and that cell stops replication. The Hayflick limit refers to the number of cell divisions at which this point is reached.

----

Part 3: The Central Dogma

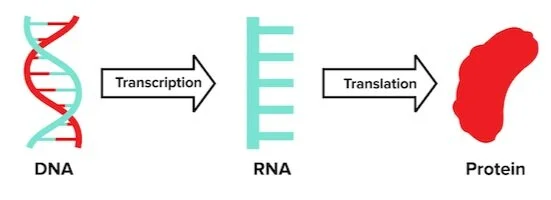

To understand why DNA is so crucial to our cells, we need to understand the central dogma of biology. Although the central dogma might sound daunting, it simply describes the relationship between DNA, RNA, and protein. The central dogma of biology states that DNA creates RNA, which in turn creates protein. We’ve drawn this relationship below for you.

Figure: The Central Dogma.

The central dogma explains how genetic information travels from storage in DNA to an intermediary RNA and finally is translated into a protein that can cause physical and chemical changes in the cell.

There are two necessary steps our cells must take to use the genetic information stored in their DNA. These steps are called transcription and translation. The cell works hard to pass on the encoded genetic information accurately at each step.

a) Transcription

Transcription is the first step of the central dogma. Transcription describes the process by which an RNA transcript is created from existing DNA. DNA and RNA use similar, but slightly different languages to encode genetic information. DNA encodes its information using four nucleotides: adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine. RNA utilizes the same nucleotides, with the exception of uracil in place of thymine. For more information, be sure to refer to our guide on RNA.

In transcription, an enzyme known as RNA polymerase acts as a translator to create a new RNA transcript. Single-copy DNA, or DNA regions that encode proteins, are transcribed by RNA polymerase. (This is in contrast to repetitive DNA, which are long regions of repetitive sequences that act as introns or protective sequences and do not encode any proteins.) The transcription of a DNA region may also be affected by transcription factors, proteins that bind to a segment of DNA to either promote or repress its transcription.

Similar to DNA polymerase, the RNA polymerase can read DNA bases and translate them into the complementary RNA sequence. Since DNA is found in the cell nucleus, that is where RNA polymerase does its work.

RNA polymerase finishes translating when it encounters a stop sequence. If all goes well, the cell has a newly synthesized strand of RNA, complementary to the template strand of the DNA and identical to the coding strand. Later on, the RNA can be used to create proteins.

b) Translation

Translation is the second step of the central dogma. Translation describes how proteins are created from synthesized RNA transcripts. Before translation can occur, synthesized RNA transcripts undergo posttranscriptional processing and are sent out of the cell nucleus. You can find more about posttranscriptional processing in our study guide on RNA.

Once the cell has mRNA transcripts, translation starts. Translation occurs in the ribosomes of cells. The ribosome binds to the mRNA transcripts and reads the codons in the RNA sequence. A codon is simply a sequence of three nucleotide bases. Each codon specifies a specific amino acid in the protein sequence. For example, the nucleotide sequence adenine, uracil, guanine represents the codon, AUG. If we look at a codon table, we’ll see that AUG specifies the amino acid methionine. The AUG codon is a start or initiation codon, which signals the ribosome to begin translation. There are additional stop codons (UAA, UGA, UAG) that signal the termination of translation.

You may note that there are more combinations of codons that are possible than there are amino acids. While there are 43, or 64 codons that can be formed by nucleotides, there are only 21 translated amino acids. As a result, multiple codons may code for the same amino acid. This is a phenomenon known as degeneracy.

For example, the amino acid alanine can be encoded by multiple codons: including GCU, GCA, GCC, GCG. You may note that while these four codons all share identical nucleotides in the first two positions, the third nucleotide does not seem to be as important. This is made possible by the wobble effect, or non-Watson Crick base pairing that allows for weak binding between the third nucleotide of the codon in mRNA and anticodon in tRNA. Thus, multiple codons can translate to the same amino acid—without requiring the presence of 64 unique tRNA molecules!

Each of the codons with an mRNA sequence has a complementary anticodon. tRNA molecules contain anticodon sequences that are able to bind their complementary codons, thus facilitating the interaction between tRNA and the ribosome. For more information on this process, be sure to refer to our guide on RNA.

Errors can occur during DNA replication, transcription, or translation. When mutations occur, the translated meaning of a codon can also be changed. A missense mutation results in the translation of a different amino acid. A nonsense mutation results in the translation of a premature stop codon, effectively truncating the translated protein.

Once the ribosome finishes reading the sequence, it has assembled a polypeptide of amino acids that can then fold into a protein.

Proteins are the expression of the genetic information contained in the DNA. Proteins carry out different functions throughout the cell based on their structure. Some proteins, such as cell membrane receptors, attach to the cell membrane and relay cell signals, while other proteins act as catalysts, breaking down waste products. It’s important to remember that while DNA might contain the information our cells need to function, proteins carry out the processes vital to the cell’s survival. You can find more information in our study guides on proteins and enzymatic function.

c) Exceptions to the central dogma

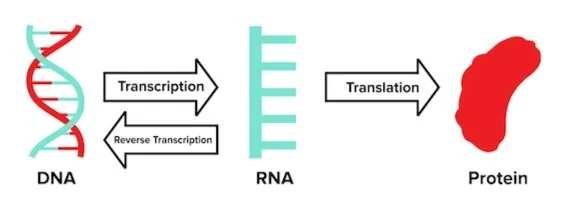

For the most part, the central dogma describes how genetic information is passed linearly from DNA to RNA to protein. There is, however, one large exception: retroviruses.

Retroviruses are RNA viruses that use a special enzyme known as reverse transcriptase to create a double-stranded DNA molecule out of the RNA they possess. Recall that the central dogma that RNA is produced using DNA as a template. Retroviruses violate this rule; instead, DNA is produced using RNA.

Human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV, is one such example of a retrovirus. Once HIV infects a cell, the virus uses a reverse transcriptase to create a DNA molecule from its RNA. The virus then uses machinery within the host cell’s nucleus to splice newly synthesized viral DNA into the host cell’s genome. This means that the HIV virus can be efficiently transcribed using the cell’s own machinery. HIV also cannot be cured without genomic editing techniques, as viral proteins would be transcribed anytime host proteins are produced.

We’ve updated the central dogma diagram from above to illustrate how retroviruses go against the linear flow of genetic information.

Figure: The revised central dogma.

Gain instant access to the most digestible and comprehensive MCAT content resources available. 60+ guides covering every content area. Subscribe today to lock in the current investments, which will be increasing in the future for new subscribers.

----

Part 4: Epigenetics and imprinting

Each of us has inherited two sets of genes: one set from our biological mother and another set from our biological father. Although we receive two sets of genes, our cells don’t necessarily express both maternal and paternal copies of each gene. Instead, our cells sometimes only express one parental copy of a gene. As a result, the genes you inherit are not necessarily the traits you express.

These changes can be partially explained through epigenetics. Epigenetic modifications are physical changes on DNA that amplify or silence the expression of certain genes. Let’s look at an example to illustrate epigenetic modifications.

Imagine driving to an important interview. While driving, you come across a construction sign that says, “Road Closed Ahead.” To avoid being late to your interview, you might choose to seek a faster detour. If you come across a speed limit sign that says, “Speed increased by 10 mph,” you’re more likely to stay on the road. The increased speed limit sign allows you to drive faster and arrive at your interview without worry. Similarly, epigenetic modifications signal the cell to either “avoid” or “approach” (e.g. suppress or express) certain genes for transcription.

Perhaps surprisingly, epigenetic modifications can also be inherited from generation to generation. Epigenetic modifications are often encoded as physical changes to the structure of DNA. During DNA replication, these physical changes are copied over from parent to offspring.

One example of epigenetic inheritance is imprinting. Imprinting occurs when an inherited copy of a gene is silenced due to epigenetic modifications passed on from parent to offspring. Imprinting can occur because of epigenetic modifications inherited from your biological father or mother. The silencing of one parental copy of a gene means that the expression of the gene is dependent on the other parental copy. Imprinting typically occurs during gamete maturation.

a) Histone structure and function

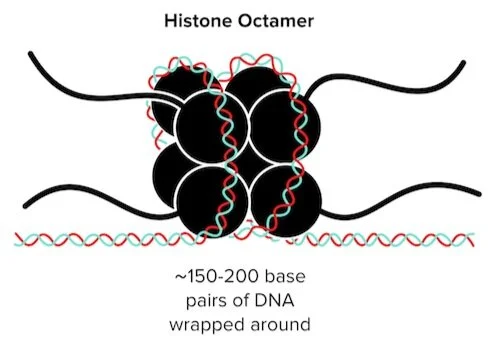

In the nucleus, DNA is organized into chromosomes. The basic organizational unit of a chromosome is known as a nucleosome. A nucleosome contains two important parts: a protein octamer known as a histone and DNA.

Figure: Histones provide organization by wrapping DNA.

A histone octamer consists of eight proteins: two H2A, two H2B, two H3, and 2H4 proteins. Around 150-200 base pairs of DNA wrap around each histone octamer. Another histone protein, known as H1, helps anchor the DNA around the histone to provide stability. This wrapped, condensed DNA is referred to as chromatin. As the genetic content of each chromosome is wrapped, homologous chromosomes become attached to each other at the centromere. (Chromatin can be further categorized into euchromatin and heterochromatin—more on this later.)

Along with organizing and condensing DNA, histones help regulate DNA expression. When it comes time to access a gene for transcription, the cellular machinery must first overcome the tightly wound DNA and histones. The relative tightness or looseness of this winding affects the degree to which each gene is expressed.

Acetylation and deacetylation

One of the most common epigenetic modifications is acetylation. Acetylation involves adding an acetyl group to lysine residues on histones. Enzymes known as histone acetyltransferases (HATs) perform this function. (While the name of this enzyme looks terrifying, note that its performance is true to its namesake—it transfers acetyl groups to histones.)

Normally, the negatively charged DNA backbone is attracted to positive lysine residues on histones. The strong electrostatic attraction between these charges prevents the cellular machinery from accessing and transcribing DNA. When lysine residues are acetylated, they lose their positive charge, reducing the interaction between DNA and histone. The attraction between the two is decreased, allowing enough space for RNA polymerase to access and transcribe the DNA. In conclusion, when histones are acetylated, gene expression for that segment of DNA is upregulated.

Perhaps intuitively, the opposite of acetylation is deacetylation. Deacetylation is performed by enzymes known as histone deacetylases (HDACs), which remove acetyl groups from lysine residues on histones. With the acetyl groups removed, the lysine residues regain their positive charges and can interact with DNA. Once again, RNA polymerase isn’t able to access the DNA to create an RNA transcript. Thus, deacetylation results in gene silencing.

One important note about acetylation and deacetylation is that the cell regulates gene expression by targeting histones instead of DNA itself. The DNA molecule itself can also be a target for gene regulation.

Methylation and demethylation

Another very common epigenetic modification is DNA methylation. Methylation involves adding methyl groups to cytosine and adenine bases in the DNA sequence. Enzymes known as DNA methyltransferases add methyl groups to DNA. The methyl groups prevent polymerases from accessing the DNA. DNA methylation occurs quite often during development to stop unnecessary genes from activating.

DNA demethylation is the reverse of methylation. Demethylation involves removing methyl groups on cytosine and adenine bases. DNA demethylase catalyzes the removal of methyl groups removed so that the genes are no longer silenced. Polymerases are free to physically access and transcribe the DNA, resulting in an upregulation of expression.

It’s important to note that these epigenetic processes can occur in cycles over a person’s lifetime. Genes can periodically be silenced or promoted, and inherited epigenetic modifications can persist for generations.

The chromatin that is wrapped around histones can be categorized by its relative ability to be read by RNA polymerase. Chromatin that can easily be read is called euchromatin (from the Latin root eu-, meaning good). Euchromatin is often under active translation and is found wrapped around acetylated histones or is demethylated.

In contrast, heterochromatin is chromatin that cannot easily be read. Heterochromatin is tightly wound and cannot easily be read.

b) X inactivation

In mammals, epigenetics plays an essential role in regulating gene expression of the X-chromosome. Can you think of a reason why regulating gene expression of the X-chromosome might be important?

Because females have two X-chromosomes, they have the potential to express more X-linked genes than the body needs. Overexpression of X-linked genes may be lethal to the proper development and function of the body. To prevent overexpression of X-linked genes, cells use epigenetic modifications to equalize the expression of X-linked genes. This process is known as X inactivation.

X inactivation involves cells randomly silencing an X-chromosome, either from the mother or father, during early female development. The selected X-chromosome becomes so heavily methylated it’s classified as heterochromatin. This inactivation helps compensate for any skewed or imbalanced expression of X-linked genes.

----

Part 5: Disorders and cancers

a) Oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes

From time to time, we all make mistakes. DNA isn’t any different. Although cells work hard to protect and accurately replicate DNA, mutations occur. If mutations or errors occur in certain genes, cancer can develop. Cancer is characterized by uncontrolled cell proliferation, lack of response to apoptotic signals (e.g., immunity to programmed cell death), and migration to different tissues in the body. Cancer can range from being mild to severe, potentially worsening over time as mutations accumulate and cells spread.

Cancer usually occurs when one of two types of genes are affected: oncogenes and suppressor genes. An oncogene is a gene that causes cancer when mutated. Normally, oncogenes—called proto-oncogenes before being mutated—play an important role in the cell cycle and promote cell growth. When a proto-oncogene is mutated, the cell is unable to control its function of promoting cell growth. As a result, the oncogene causes uncontrollable cell proliferation—one of the key characteristics of cancer. Oncogene mutations are dominant, meaning that one mutated allele of an oncogene is sufficient to cause cancer.

The body has a natural defense system against tumor growth in tumor suppressor genes. A tumor suppressor gene is a gene that inhibits cell cycle progression and marks cells for apoptosis. When mutated, tumor suppressor genes lose their inhibitory function, thus allowing cells that shouldn’t survive to grow. As a result, tumors and cancer develop. Unlike oncogene mutations, both alleles of a tumor suppressor gene must be mutated to cause loss of function. One functioning allele of a tumor suppressor gene is sufficient to inhibit cell cycle progression.

b) Chromosomal defects

Errors in DNA can vary from replication-level mismatches to chromosomal defects. In chromosomal defects, cells have an abnormal number of chromosomes because of errors in meiosis. Two examples of chromosomal defects are trisomy 21 and Klinefelter syndrome.

In trisomy 21, Down syndrome, affected individuals have an extra chromosome 21. Individuals with trisomy 21, or Down Syndrome, often face varying levels of growth delays, cognitive impairment, and social stigma. The extra chromosome occurs due to meiotic errors in the formation of gametes from the mother or father, which results in the offspring inheriting three copies of chromosome 21. During meiosis, chromosome 21 was not able to successfully separate from its pair. This failure to separate is known as nondisjunction.

In Klinefelter syndrome, affected individuals have two X-chromosomes and one Y-chromosome. Similar to trisomy 21, nondisjunction in meiosis results in gametes with two sex chromosomes instead of one. The offspring has the karyotype XXY. Individuals born with Klinefelter syndrome can have varying symptoms from reduced muscle mass to enlarged breast tissue to infertility.

----

Part 6: High-yield terms

Double helix: structure of DNA; two strands of DNA wrap around each other and form a twisted ladder pattern

Nucleotides: bonded DNA pairs that include adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine

Purines: aromatic nitrogenous bases with two rings; include adenine and guanine

Pyrimidines: aromatic nitrogenous bases with one ring; include cytosine and thymine

Watson-Crick base pairing: bonding rules under which adenine exclusively bonds with thymine and cytosine exclusively bonds with guanine

Sugar phosphate backbone: a repeating pattern of pentose sugar and phosphate groups bonded together; in DNA, the sugar is deoxyribose

G-C content: a measure of the percentage of nucleotide bases that contain guanine or cytosine in a fragment of DNA; high G-C content indicates higher melting point

Melting point: the temperature at which hydrogen bonds between base pairs are disrupted and the two strands of DNA are dissociated

Chargaff’s rules: state that the ratio of purine nucleotides to pyrimidine nucleotides in DNA is 1 to 1. In fact, the ratio of guanine nucleotides to cytosine nucleotides and the ratio of adenine nucleotides to thymine nucleotides are also each 1 to 1

Antiparallel: describes the two strands of DNA that run in opposite directions (5’ to 3’ and 3’ to 5’)

Origin of replication: a sequence rich in adenine-thymine bonds at which the replisome is initially formed

Helicase: an enzyme that unzips DNA strands during replication

DNA topoisomerase: an enzyme that relaxes the coiling in DNA by making selective cuts in the phosphate backbone and repairing them

DNA primase: an enzyme that creates a short strand of RNA that is complementary to DNA

DNA polymerase: an enzyme that replaces RNA primers, continuously adds nucleotides to the daughter strand, and conducts proofreading during DNA synthesis

Ligase: an enzyme that seals sequences of nucleotides together during DNA synthesis

Leading strand: the template strand used during DNA synthesis, running in the 3’ to 5’ direction

Lagging strand: the strand complementary to the lagging strand; runs in the 5’ to 3’ direction

Okazaki fragments: short sequences of DNA that are produced in spurts along the lagging strand

Mismatch repair: occurs in the G2 phase of the cell cycle to correct any leftover errors from synthesis

Transcription: the process by which an RNA transcript is created from existing DNA; RNA polymerase creates RNA strands that are complementary to the template strand of DNA

Translation: describes how proteins are created from synthesized RNA transcripts; occurs in ribosomes

Retroviruses: RNA viruses that use a special enzyme known as a reverse transcriptase to create a double-stranded DNA molecule out of the RNA they possess

Epigenetic modifications: physical changes on DNA that amplify or silence the expression of certain genes; include histone acetylation and deacetylation and DNA methylation and demethylation

Imprinting: occurs when an inherited copy of a gene is silenced due to epigenetic modifications passed on from parent to offspring

Nucleosome: a protein octamer known as a histone, and DNA

Histone acetyltransferases (HATs): enzymes that transfer acetyl groups to histones and function in the upregulation of gene expression

DNA methyltransferases: enzymes that add methyl groups to DNA and function in the deactivation of genes

Euchromatin: chromatin that is relatively relaxed and can easily be read

Heterochromatin: chromatin that is relatively dense and cannot easily be read

X inactivation: involves cells randomly silencing an X-chromosome, either from the mother or father, during early female development

Cancer: characterized by uncontrolled cell proliferation, lack of response to apoptotic signals (e.g. immunity to programmed cell death), and migration to different tissues in the body

Oncogene: a gene that causes cancer when mutated

Tumor suppressor gene: a gene that inhibits cell cycle progression and marks cells for apoptosis

Nondisjunction: failure of pairs of chromosomes to separate during meiosis; can result in chromosomal disorders such as trisomy 21 and Klinefelter syndrome

Looking for MCAT Practice Questions? Check out our proprietary MCAT Question Bank for 4000+ sample questions and eight practice tests covering every MCAT category.

Gain instant access to 4,000+ representative MCAT questions across all four sections to identify your weaknesses, bolster your strengths, and maximize your score. Subscribe today to lock in the current investments, which will be increasing in the future for new subscribers.

----

Part 7: Passage-based questions and answers

The study of non-model bacteria can increase the range of applications of synthetic biology. There is currently limited availability of biological components for the genetic circuits in non-model species of bacteria. As a result, scientists are increasingly interested in mining bacteriophages for the components of genetic circuits in non-model bacteria.

The components of genetic circuits within non-model bacteria include: (1) a promoter region, which allows for increased control in inducing gene expression; (2) ribosomal binding sites, which further adjust expression levels; (3) terminators, which signal the end of transcription and thus avoid interference from nearby promoter regions; and (4) RNA-based parts, which further regulate genetic circuits.

In a new study, scientists are interested in developing genetic circuits for Lactococcus lactis, a non-model bacteria that has exhibited experimental success as an in vivo delivery vehicle for oral vaccines and other therapeutic products. To do so, the researchers will first produce ten cultures of Lactococcus lactis.

CREATOR AND ATTRIBUTION PARTY: LAMMENS, E., NIKEL, P.I. & LAVIGNE, R. EXPLORING THE SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY POTENTIAL OF BACTERIOPHAGES FOR ENGINEERING NON-MODEL BACTERIA. NAT COMMUN 11, 5294 (2020). THE ARTICLE’S FULL TEXT IS AVAILABLE HERE: HTTPS://WWW.NATURE.COM/ARTICLES/S41467-020-19124-X. THE ARTICLE IS NOT COPYRIGHTED BY SHEMMASSIAN ACADEMIC CONSULTING. DISCLAIMER: SHEMMASSIAN ACADEMIC CONSULTING DOES NOT OWN THE PASSAGE PRESENTED HERE. CREATIVE COMMONS LICENSE: HTTP://CREATIVECOMMONS.ORG/LICENSES/BY/4.0/. CHANGES WERE MADE TO ORIGINAL ARTICLE TO CREATE AN MCAT-STYLE PASSAGE.

Question 1: Which of the following statements is true and will enhance the function of the genetic circuit?

A) If the promoter’s cytosine and adenine groups are demethylated, the addition of DNA methylase will methylate the promoter region and enhance levels of transcription

B) If the promoter’s thymine and guanine groups are methylated, the addition of DNA demethylase will demethylate the promoter region and enhance levels of transcription

C) If the promoter’s thymine and guanine groups are demethylated, the addition of DNA methylase will methylate the promoter region and enhance levels of transcription

D) None of the above

Question 2: While maintaining the Lactococcus lactis cell cultures, Scientist A accidentally adds an unlabeled tube to Culture 6. Subsequent gel electrophoresis analysis of the culture’s DNA shows its molecular weight to be less than half of that of the original sample. Which enzymes were most likely present in the tube?

A) DNA polymerase and DNA ligase

B) DNA helicase and DNA ligase

C) DNA polymerase and DNA nuclease

D) DNA helicase and DNA nuclease

Question 3: If the amount of cytosine in a given terminator region is 32%, what is the amount of adenine in this region?

A) 36%

B) 18%

C) 32%

D) 16%

Question 4: Which of the following could represent the leading strand of a terminator sequence and its newly synthesized DNA complement?

A) Leading strand: 5’ CATCC GTTGG CTATG CTTAAG TATCG 3’

Newly synthesized strand: 3’ GTAGG CAACC GATAC GAATTC ATAGC 5’

B) Leading strand: 5’ CATCC GTTGG CTATG CTTAAG TATCG 3’

Newly synthesized strand: 3’ GUAGG CAACC GAUAC GAAUUC AUAGC 5’

C) Leading strand: 3’ CATCC GTTGG CTATG CTTAAG TATCG 5’

Newly synthesized strand: 5’ GTAGG CAACC GATAC GAATTC ATAGC 3’

D) Leading strand: 5’ CATCC GTTGG CTATG CTTAAG TATCG 3’

Newly synthesized strand: 3’ GUAGG CAACC GAUAC GAAUUC AUAGC 5’

Answers to passage-based questions

Answer choice D is correct. Methyl groups added to cytosine and adenine can inhibit transcription. As a result, the addition of methylase to methylate these groups will not enhance levels of transcription but rather inhibit it (choices A and C are incorrect). As DNA methylation primarily occurs at cytosine and adenine bases, demethylation of thymine and guanine groups is not expected to affect transcription levels (choice B is incorrect).

Answer choice D is correct. Given the lower molecular weight, the enzymes in the unlabeled tube likely cleaved or degraded the DNA present in the cell culture. DNA polymerase synthesizes new strands of DNA, and DNA ligase joins fragments of DNA together (choices A, B, and C are incorrect). DNA helicase unwinds DNA, which would then allow DNA nuclease to degrade single-stranded DNA (choice D is correct).

Answer choice B is correct. According to Chargaff’s rules, there are equal amounts of cytosine and guanine and equal amounts of adenine and thymine present in DNA. If there is 32% cytosine, then the amount of guanine would also be 32%, implying that the DNA is 64% G or C bases. The total amount of adenine and thymine must then be 36%. As the amount of adenine in DNA must equal the amount of thymine, the DNA composition must be 36%/2 = 18% adenine (choice B is correct).

Answer choice C is correct. DNA polymerase reads the leading strand in the 3’ to 5’ direction and synthesizes DNA in the 5’ to 3’ direction (choices A and B are incorrect). While RNA contains uracil as a nucleotide, DNA does not (choice D is incorrect).

----

Part 8: Standalone practice questions and answers

Question 1: What kind of bond exists in the sugar phosphate backbone?

A) Hydrogen bond

B) Peptide bond

C) Glycosidic bond

D) Phosphodiester bond

Question 2: What is the primary difference between transcription and translation?

A) Transcription describes the process of creating RNA from DNA, while translation describes how DNA is synthesized.

B) Transcription describes the process of creating protein from RNA, while translation describes the process of creating RNA from DNA.

C) Transcription describes the process of creating RNA from DNA, while translation describes the process of creating protein from RNA.

D) Transcription describes how DNA is synthesized, while translation describes the process of creating protein from RNA.

Question 3: Why is the origin of replication rich in adenine-thymine nucleotide base pairs?

A) Adenine and thymine are only bonded by two hydrogen bonds, making bonds between them easier to disrupt.

B) Adenine and thymine are only bonded by three hydrogen bonds, making bonds between them easier to disrupt.

C) The positive charges on adenine and thymine attract the enzyme that cuts the origin of replication.

D) Adenine and thymine are only methylated, making their bond easier to disrupt.

Question 4: Which of the following structures would be found paired with a thymine base?

A)

B)

C)

D)

Question 5: Scientists want to silence a particular gene in a DNA sample they isolated. How could they go about silencing the gene?

A) Scientists could promote demethylation of the DNA and deacetylation of the histones using methylases and histone deacetylases, respectively.

B) Scientists could promote methylation of the DNA and deacetylation of the histones using methylases and histone deacetylases, respectively.

C) Scientists could promote methylation of the DNA and acetylation of the histones using methylases and histone acetyltransferases, respectively.

D) Scientists could promote demethylation of the DNA and acetylation of the histones using demethylases and histone acetyltransferases, respectively.

Answer key for practice questions

1. Answer choice D is correct. Right off the bat, we know that hydrogen bonds (A) aren’t the answer because hydrogen bonds exist between nucleotide pairs, not the backbone. Peptide bonds (B) exist in proteins, but DNA is a nucleic acid. Glycosidic (C) bonds exist between the pentose sugar and the base of a nucleotide. Phosphodiester bonds (D) is the answer because the sugar phosphate backbone of DNA is connected by phosphate groups bonded to the adjacent pentose sugar.

2. Answer choice C is correct. Transcription is the process of creating RNA from DNA, while translation is the process of creating protein from RNA. DNA replication is the process of synthesizing new DNA (choices A and D are incorrect).

3. Answer choice A is correct. The origin of replication describes where DNA replication starts. A break in the DNA must be made for replication to occur. Adenine and thymine bonds are the weaker of the two nucleotide bonds because there are only two hydrogen bonds (choice A is correct). Cytosine and guanine base pairs are bonded by three hydrogen bonds (choice B is incorrect). Electrostatic attraction does not play a significant role in DNA synthesis (choice C is incorrect). Methylation plays a role in epigenetics and gene signaling (choice D is incorrect).

4. Answer choice B is correct. Recall that thymine binds with adenine; thus, we are looking for an answer option that depicts the structure of adenine. From our discussion, we know adenine is a purine with a two-ring structure (choices A and D are incorrect). Adenine lacks a carbonyl group as well (choice C is incorrect). It’s important to have the structures of the different bases memorized.

5. Answer choice B is correct. To silence a gene, scientists can methylate DNA; methyl groups prevent transcription or deacetylate histones to promote histone-DNA bonding. Acetylation of histones generally promotes gene expression (choices C and D are incorrect). Demethylation of DNA also generally promotes gene expression (choice A is incorrect).